Treasured Items of Bungalow Club Members

Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.

—William Morris

This collection features photos and descriptions of items treasured by Twin Cities Bungalow Club members. Each of us has a favorite item or two (or more) in our bungalow. Since the Bungalow Club cannot meet for the time being due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we have created a place to share member’s favorite items online.

Additional images and descriptions will be added as we receive them from members. If you have questions about what to submit or about how to take a quality photo, we offer some guidelines.

We want to hear from you. Send a color photo and description to mail@bungalowclub.net, or mail to: Twin Cities Bungalow Club, 3547 24th Avenue S., Minneapolis, MN 55406.

Submissions from Twin Cities Bungalow Club members only, please.

Newman Brother’s Co. floor-style phonograph, submitted by Michael Melmer-Damon

This floor-style phonograph once belonged to my great-grandfather on my mother’s side. He died before I was born, but it remained in his farmhouse in Belmond, Iowa, and was passed on to my grandmother. When my family visited when I was a kid, I’d make a beeline for the second-floor storage room where it stood.

This floor-style phonograph once belonged to my great-grandfather on my mother’s side. He died before I was born, but it remained in his farmhouse in Belmond, Iowa, and was passed on to my grandmother. When my family visited when I was a kid, I’d make a beeline for the second-floor storage room where it stood.

I spent hours in that small room, playing the vintage records that were stored in the cabinet below the turntable. It was like tapping into a different era, another time. The earliest disks dated from the 1920s and included blues legend Bessie Smith’s first record; a recording of comedian Myron Cohen; and records by Vaughn De Leath, who was known as “The Original Radio Girl.”

I was a teenager in the 1960s when the family gave the phonograph to me. It was a good thing, because shortly afterward, an F5 level tornado swept through Belmond, destroying more than 100 homes and 75 businesses. My grandmother’s house was blown off its foundation; its contents left in shambles.

The phonograph now resides in a corner of our bungalow’s dining room. Sometimes I crank it up—for example, when the electricity goes out in the summertime. I open all the windows and let the music waft through the neighborhood.

Skyscraper lamps, submitted by Kathleen Varner

About 20 years ago, my friend Deb and her sister snuck into their parents’ basement while the parents were out of town. The basement was a hoarder’s den, stuffed with all manner of furniture, accessories, and decorative items. The weekend goal was to divest them of several items and rearrange the stash without the parents noticing. Among the treasures was a pair of Art Deco period table lamps, commonly known as “skyscraper” lamps. Deb thought I would appreciate these unusual lamps, so would I like to have them? Yes!

About 20 years ago, my friend Deb and her sister snuck into their parents’ basement while the parents were out of town. The basement was a hoarder’s den, stuffed with all manner of furniture, accessories, and decorative items. The weekend goal was to divest them of several items and rearrange the stash without the parents noticing. Among the treasures was a pair of Art Deco period table lamps, commonly known as “skyscraper” lamps. Deb thought I would appreciate these unusual lamps, so would I like to have them? Yes!

Skyscraper-shape lamps were designed circa 1930s to depict the ever growing popularity of big city skyscrapers. The lamps are made of multicolored plastic; stand 21 inches tall; and have a round base measuring 6.7 inches in diameter. Two buttons are on each base: red to turn on, black for off. Upright fluorescent bulbs light from within. I had the frayed cloth cords replaced with fabric cords at Moen Electric.

Using a mark on the bottom of each lamp, I was able to search the internet for the manufacturer. These lamps were made in Chicago by the Carl Swanson Lite Manufacturing Company in the 1930s.

My lamps are placed on either end of my sideboard in my dining room. Fun fact: This model was shown in the movie Aviator on the desk of Howard Hughes, played by Leonardo DiCaprio.

Pyrography wastepaper basket, submitted by Kathleen Varner

About 25 years ago, I went to a neighborhood estate sale. In a back room in a corner, I noticed an unusual four-sided wooden receptacle. The estate agent did not know what the purpose of the piece was but we surmised its intended function was as an umbrella stand, due to its shape and its height of 16 ½ inches. Each of the four sides was held together by leather lashing. Pyrography (the art of wood burning), along with hand painting, was used to adorn each side with clusters of grapes and leaves in shades of purple, gold, and green.

About 25 years ago, I went to a neighborhood estate sale. In a back room in a corner, I noticed an unusual four-sided wooden receptacle. The estate agent did not know what the purpose of the piece was but we surmised its intended function was as an umbrella stand, due to its shape and its height of 16 ½ inches. Each of the four sides was held together by leather lashing. Pyrography (the art of wood burning), along with hand painting, was used to adorn each side with clusters of grapes and leaves in shades of purple, gold, and green.

I peered into the bottom of the piece and inside, carved in the base, was a date: February 21, 1905. Almost 100 years old! I purchased this piece for $10. Ever since, it has served as my wastepaper basket in my office, next to my Mission style desk.

World’s Fair Statue of Liberty clock/lamp, submitted by Deb McKinley

My mom traveled with family from Alabama to the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair when she was 16 years old. She got to “view the marvels of the greatest expedition in history” at the second most expensive—$150 million—American world’s fair. Whenever she talked about the trip, she always mentioned the parachute jump thrill ride. (Get a glimpse of the ride in this vintage newsreel—about five minutes into the newsreel.)

My mom traveled with family from Alabama to the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair when she was 16 years old. She got to “view the marvels of the greatest expedition in history” at the second most expensive—$150 million—American world’s fair. Whenever she talked about the trip, she always mentioned the parachute jump thrill ride. (Get a glimpse of the ride in this vintage newsreel—about five minutes into the newsreel.)

This world’s fair was supposed to look toward the future—the “World of Tomorrow”—and all the promises that science, technology, democracy, and collective effort could bring. World War II erupted during this period. Perhaps this world of tomorrow is one reason she married my father, a mechanical and electrical engineer who literally became a rocket scientist.

The metal Statue of Liberty with clock and night light (both still work) was a souvenir from her trip. Around Lady Liberty’s neck is another souvenir, a charm bracelet with letters spelling “NY WORLDS FAIR 1939.”

River stone birdbath, submitted by Mike Lazaretti

I purchased this birdbath, made of concrete and smooth stones, more than 10 years ago at Mother Earth Gardens in Minneapolis (motherearthgarden.com). It was made in Mexico and is not vintage, but it has a rustic style that reminds me of handmade garden items from the bungalow era. I assumed it would fall apart before long. After all, Minnesota winters, with their repeating freeze-thaw cycles, are not kind to masonry work of any kind. But I store the birdbath in a shed during the winter, and it has held up astonishingly well—the rocks are still firmly in place and the concrete is solid.

I purchased this birdbath, made of concrete and smooth stones, more than 10 years ago at Mother Earth Gardens in Minneapolis (motherearthgarden.com). It was made in Mexico and is not vintage, but it has a rustic style that reminds me of handmade garden items from the bungalow era. I assumed it would fall apart before long. After all, Minnesota winters, with their repeating freeze-thaw cycles, are not kind to masonry work of any kind. But I store the birdbath in a shed during the winter, and it has held up astonishingly well—the rocks are still firmly in place and the concrete is solid.

Cast iron lamp, submitted by Gail Tischler

This heavy cast iron table lamp with green slag glass sat in the parlor of my maternal great grandparents’ Minnesota farm home. When I visited the farm as a child, that room was off limits—the door was kept shut to protect all the things my great grandparents cherished.

This heavy cast iron table lamp with green slag glass sat in the parlor of my maternal great grandparents’ Minnesota farm home. When I visited the farm as a child, that room was off limits—the door was kept shut to protect all the things my great grandparents cherished.

Originally a kerosene-burning lamp, we had it electrified at the Let There Be Light shop in Stillwater (now open by appointment only). The owner, Steve, was able to do this alteration and still keep most of the metal kerosene-related parts, AND we can still insert the glass chimney. In doing so, the lamp kept its original look. Steve also replaced several cracked pieces of the glass. Slag glass, also known as marble glass or malachite glass, is a type of opaque pressed glass with creamy-colored swirling. The lamp may be a Bradley & Hubbard. It is identical in style to a lamp made by them from 1900 to 1919, but we have not found a mark to verify the maker. It could simply be an early 20th century parlor version of a more expensive lamp. The green slag glass is lovely when lit and sits where we can see it every day.

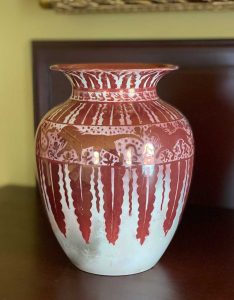

Red Wing vase with Nokomis Glaze, submitted by Liz Blood

My parents received this vase as a gift when they were married in 1931. After living in their South Minneapolis home for 40 years, they went through the process of giving some of their treasured possessions to family members. I received this vase. A few years ago the Twin Cities Bungalow Club organized a bus tour to the Red Wing pottery museum in Red Wing, Minnesota. I was thrilled to see a similar vase in their collection and learned that the multicolored glaze is called the “Nokomis Glaze.” Red Wing Pottery’s records show that the glaze was only made for a few years in the early 1930s. Apparently it had a high lead content, which may be the reason it was used only a short time. Before passing it on, my mother told me I could have the vase if I promised not to sell it. I have no intention of doing that, of course. I treasure it.

My parents received this vase as a gift when they were married in 1931. After living in their South Minneapolis home for 40 years, they went through the process of giving some of their treasured possessions to family members. I received this vase. A few years ago the Twin Cities Bungalow Club organized a bus tour to the Red Wing pottery museum in Red Wing, Minnesota. I was thrilled to see a similar vase in their collection and learned that the multicolored glaze is called the “Nokomis Glaze.” Red Wing Pottery’s records show that the glaze was only made for a few years in the early 1930s. Apparently it had a high lead content, which may be the reason it was used only a short time. Before passing it on, my mother told me I could have the vase if I promised not to sell it. I have no intention of doing that, of course. I treasure it.

GE “monitor top” refrigerator clock, submitted by Bill Blood (“This Old Handyman”)

This clock is an 8½-inch-tall replica of the General Electric “monitor top,” the first widely available consumer refrigerator, which had its compressor mounted on top. The monitor top was an immediate success when it was introduced in 1927, thanks in part to an aggressive advertising campaign that included this clock. I started looking for one several years ago. I came across other promotional items including salt and pepper shakers shaped like the refrigerator and tape measures bearing an image of the appliance. But the clocks are much rarer. Eventually a friend found one on eBay, dated 1928, which my wife bought for my birthday. It arrived; I fired it up; and it worked for 45 minutes. Then it stopped, never to run again. I turned it over to an antique clock dealer for repair, but he had difficulty finding parts. He died and all his clocks, including mine, disappeared. More than a year later I found a second clock in Wisconsin. It didn’t work, so I took it to a jeweler, who converted it to battery power. Much of the paint had flaked off its metal body, so I refinished it. I look at it lovingly several times a day.

Cigarette lighter, submitted by Barbara Benner

Family lore says that my maternal grandfather “won” this Ronson brand cigarette lighter from a claw machine in Atlantic City. It is in the form of Abraham Lincoln seated on a bench. The striker wand is inserted in a well that once contained lighter fluid. More than 70 years after my grandfather’s death, it still smells of lighter fluid.

Family lore says that my maternal grandfather “won” this Ronson brand cigarette lighter from a claw machine in Atlantic City. It is in the form of Abraham Lincoln seated on a bench. The striker wand is inserted in a well that once contained lighter fluid. More than 70 years after my grandfather’s death, it still smells of lighter fluid.

Arts & Crafts-style chairs, submitted by Deborah Smith

These chairs belonged to my husband’s grandparents, who bought them in the early 1920s. The wood is mahogany, and according to a label on the bottom of one of the chairs, they were made by the Levin Bros. company, located in southeast Minneapolis. We rescued them from a relative’s storage shed, and had them reupholstered in leather. We originally had a matching hide-a-bed, but sadly, we had to get rid of it because we could not get it into our first, very small bungalow. I am very happy that we at least have the chairs!

These chairs belonged to my husband’s grandparents, who bought them in the early 1920s. The wood is mahogany, and according to a label on the bottom of one of the chairs, they were made by the Levin Bros. company, located in southeast Minneapolis. We rescued them from a relative’s storage shed, and had them reupholstered in leather. We originally had a matching hide-a-bed, but sadly, we had to get rid of it because we could not get it into our first, very small bungalow. I am very happy that we at least have the chairs!

Art Deco-style light fixture, submitted by Susan Kennedy

This Art Deco-style dining room light fixture is a bit newer than my 1912 house, but I love the look. My house was originally piped for gas fixtures, so the light fixtures were probably upgraded to all-electric versions in the 1930s. There is a matching ceiling fixture in the living room, and an extra glass slipper shade is still stored in the dining room buffet.

This Art Deco-style dining room light fixture is a bit newer than my 1912 house, but I love the look. My house was originally piped for gas fixtures, so the light fixtures were probably upgraded to all-electric versions in the 1930s. There is a matching ceiling fixture in the living room, and an extra glass slipper shade is still stored in the dining room buffet.

Trench art lamp, submitted by Barbara Benner

The shaft of this “trench art” lamp is made from an artillery shell. It was carried home by my paternal grandfather in his knapsack after serving in WWI, where he survived the deadly Meuse-Argonne offensive near the end of the war. He told my father that it was made by wounded French soldiers. Though my grandfather died when I was very young, I remember the lamp from my childhood. After I finished graduate school and bought a house, my father passed the lamp to me. I bought the Tiffany-style shade as a birthday present to myself almost 30 years ago.

The shaft of this “trench art” lamp is made from an artillery shell. It was carried home by my paternal grandfather in his knapsack after serving in WWI, where he survived the deadly Meuse-Argonne offensive near the end of the war. He told my father that it was made by wounded French soldiers. Though my grandfather died when I was very young, I remember the lamp from my childhood. After I finished graduate school and bought a house, my father passed the lamp to me. I bought the Tiffany-style shade as a birthday present to myself almost 30 years ago.

Sewing machine cabinet, submitted by Deborah Smith

Having grown tired of the 1950s cabinet holding my sewing machine, I discovered this perfect-for-our-1925-bungalow cabinet, made in 1918, on Craigslist. It was offered by a woman in Fridley, Minnesota, who said it belonged to her grandmother. The woman had used it as a side table for years and was delighted to hear it was to return it to its original purpose. My husband, Bob, installed a spring-loaded “elevator” mechanism so that my modern sewing machine emerges from the top and locks at two levels. He also made pull-out shelves with pegs for thread spools. The cabinet’s center panel is hinged at the top so that it swings inward and upward to make room for my knees.

Having grown tired of the 1950s cabinet holding my sewing machine, I discovered this perfect-for-our-1925-bungalow cabinet, made in 1918, on Craigslist. It was offered by a woman in Fridley, Minnesota, who said it belonged to her grandmother. The woman had used it as a side table for years and was delighted to hear it was to return it to its original purpose. My husband, Bob, installed a spring-loaded “elevator” mechanism so that my modern sewing machine emerges from the top and locks at two levels. He also made pull-out shelves with pegs for thread spools. The cabinet’s center panel is hinged at the top so that it swings inward and upward to make room for my knees.

Diamond ring, submitted by Susan Kennedy

This elegant ring was in my mother’s jewelry box, which I received after she died. I don’t recall her wearing it, but it is sized for a very large knuckle, as her mother and siblings suffered from rheumatoid arthritis. A jeweler’s appraisal came with the ring, which reads in part, “14k white gold ladies ring, mounted with one .05 diamond.” It is not very valuable but I like its style, especially the filigree on the band, which has been repaired.

This elegant ring was in my mother’s jewelry box, which I received after she died. I don’t recall her wearing it, but it is sized for a very large knuckle, as her mother and siblings suffered from rheumatoid arthritis. A jeweler’s appraisal came with the ring, which reads in part, “14k white gold ladies ring, mounted with one .05 diamond.” It is not very valuable but I like its style, especially the filigree on the band, which has been repaired.

Seth Thomas mantel clock, submitted by Marty Moen

This 14.5-inch-tall, red-oak- veneered clock is a valued Arts & Crafts item in our house. After 100 years, it continues to keep time with remarkable accuracy. Chimes ring on the hour and its cup bell rings on the half hour. I enjoy hearing the mellow sound throughout the day that only a vintage clock can provide.

This 14.5-inch-tall, red-oak- veneered clock is a valued Arts & Crafts item in our house. After 100 years, it continues to keep time with remarkable accuracy. Chimes ring on the hour and its cup bell rings on the half hour. I enjoy hearing the mellow sound throughout the day that only a vintage clock can provide.

Bronze dead bird sculpture, submitted by Tim Counts

I bought this piece during the early days of eBay because I thought it was odd. The display box provides some information about its journey. Inside the box, printed in gold ink on the satin pad next to the bird, are words indicating it was manufactured in Paris by a company named Susse Fréres. Inside the box’s lid, we see that it was handled by a company named French Decorative Art Ltd., located on Bond Street in London. Finally, on the box lid’s exterior are the words Ritz Carlton, New York, 1910-1911. So, why would some reasonably well-to-do person purchase a dead bird sculpture in a Ritz Carlton hotel? And why would an upscale hotel offer such an item? It is hard to say, viewing it through today’s sensibilities. Perhaps it was meant to remind one that despite life’s beauty, we must never forget its fragility and temporal nature.

I bought this piece during the early days of eBay because I thought it was odd. The display box provides some information about its journey. Inside the box, printed in gold ink on the satin pad next to the bird, are words indicating it was manufactured in Paris by a company named Susse Fréres. Inside the box’s lid, we see that it was handled by a company named French Decorative Art Ltd., located on Bond Street in London. Finally, on the box lid’s exterior are the words Ritz Carlton, New York, 1910-1911. So, why would some reasonably well-to-do person purchase a dead bird sculpture in a Ritz Carlton hotel? And why would an upscale hotel offer such an item? It is hard to say, viewing it through today’s sensibilities. Perhaps it was meant to remind one that despite life’s beauty, we must never forget its fragility and temporal nature.

Tudric vase designed by Oliver Baker, submitted by Tim Counts

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Liberty & Co. department store in London often collaborated with the hottest designers of the day, including such luminaries as William Morris and Dante Gabriel Rosetti. Among Liberty’s exclusive lines of decorative objects was Tudric pewterware, introduced in 1899 and continuing into the 1930s. I purchased this 14-inch-tall Tudric vase with two handles at Liberty in 2000. At the top is a design of stylized acorns and oak leaves. Though Liberty discontinued the line long ago, they had re-purchased some of their own objects from antiques dealers; then re-sold them in their store. Though I probably paid more for this than I might have in another setting, I loved the idea of buying it in the same store where it had originally sold a century before.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Liberty & Co. department store in London often collaborated with the hottest designers of the day, including such luminaries as William Morris and Dante Gabriel Rosetti. Among Liberty’s exclusive lines of decorative objects was Tudric pewterware, introduced in 1899 and continuing into the 1930s. I purchased this 14-inch-tall Tudric vase with two handles at Liberty in 2000. At the top is a design of stylized acorns and oak leaves. Though Liberty discontinued the line long ago, they had re-purchased some of their own objects from antiques dealers; then re-sold them in their store. Though I probably paid more for this than I might have in another setting, I loved the idea of buying it in the same store where it had originally sold a century before.

Embroidered pillow, submitted by Tim Counts

In the early days of the Arts & Crafts revival, I collected many vintage textiles embroidered with beautiful designs. This pillow is special, though. It features a butterfly or moth design embroidered on linen using a high-relief loop stitch. The technique really makes the design pop. It is displayed in my bungalow’s living room, resting in an antique Mission style rocking chair.

In the early days of the Arts & Crafts revival, I collected many vintage textiles embroidered with beautiful designs. This pillow is special, though. It features a butterfly or moth design embroidered on linen using a high-relief loop stitch. The technique really makes the design pop. It is displayed in my bungalow’s living room, resting in an antique Mission style rocking chair.

Felix the Cat toy, submitted by Tim Counts

Felix was a popular figure in the early 1920s, starring in cartoons and a comic strip. Fans could buy toy versions of Felix, made of stuffed fabric, metal or wood. This 4-inch-tall figure is made of painted wood pieces held together with string. A label on the bottom of one foot indicates it was patented in 1925—one year before my bungalow was built.

Felix was a popular figure in the early 1920s, starring in cartoons and a comic strip. Fans could buy toy versions of Felix, made of stuffed fabric, metal or wood. This 4-inch-tall figure is made of painted wood pieces held together with string. A label on the bottom of one foot indicates it was patented in 1925—one year before my bungalow was built.

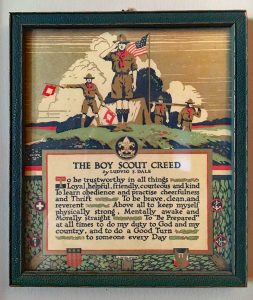

Buzza motto, submitted by Deb McKinley

Some objects come to you sideways and land right where they belong. That is how “The Boy Scout Creed” Buzza motto ended up in the dining room of my 1924 bungalow. Growing up in Ohio, my mom would send us kids two doors down to visit our widowed neighbor Margaret. She became a friend to us, as did her brother “Doc.” I thought of Doc as the grandfather I never knew. When he died, I received a few of his possessions, including this framed print. Fast forward 20 years when I learned at a Twin Cities Bungalow Club event this print of Doc’s was a Buzza motto. George Buzza founded his greeting card company in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 1909, which also printed framed sentimental mottos. The boy scout print came back to where it was printed and to a house built in the same decade.

Some objects come to you sideways and land right where they belong. That is how “The Boy Scout Creed” Buzza motto ended up in the dining room of my 1924 bungalow. Growing up in Ohio, my mom would send us kids two doors down to visit our widowed neighbor Margaret. She became a friend to us, as did her brother “Doc.” I thought of Doc as the grandfather I never knew. When he died, I received a few of his possessions, including this framed print. Fast forward 20 years when I learned at a Twin Cities Bungalow Club event this print of Doc’s was a Buzza motto. George Buzza founded his greeting card company in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 1909, which also printed framed sentimental mottos. The boy scout print came back to where it was printed and to a house built in the same decade.

Pottery and copper lamp, submitted by Tim Counts

I purchased this lamp in an eBay auction way back in the 1990s. It was not cheap, but one look at the online photos, and I was smitten. The base is made by Weller Pottery. The shade is comprised of panels of thin copper riveted together. The tree and hills design was created by punching thousands of small holes in the copper, allowing the lamp light to shine through. The lamp retains its kerosene fount, which rests inside the base, and a wick mechanism with a glass chimney on top. I intended to have the lamp wired for electricity. But as soon as I unpacked it, I rigged up a temporary bulb socket on a cord and taped it to the backside of the lamp, just to see how it would look all lit up. It’s still there.

I purchased this lamp in an eBay auction way back in the 1990s. It was not cheap, but one look at the online photos, and I was smitten. The base is made by Weller Pottery. The shade is comprised of panels of thin copper riveted together. The tree and hills design was created by punching thousands of small holes in the copper, allowing the lamp light to shine through. The lamp retains its kerosene fount, which rests inside the base, and a wick mechanism with a glass chimney on top. I intended to have the lamp wired for electricity. But as soon as I unpacked it, I rigged up a temporary bulb socket on a cord and taped it to the backside of the lamp, just to see how it would look all lit up. It’s still there.

Vase attributed to Maw & Co., submitted by Mike Lazaretti

I purchased this 7-inch-tall vase at the Liberty & Co. department store in London in December, 2015. At the time, Liberty had a small section devoted to antiques, many of them from the English Arts & Crafts period. Maw & Co. was launched in 1850 and primarily produced high-end wall and floor decorative tiles. In the 1890s, they introduced a line of hand-painted art pottery, of which this is a beautiful example. The vase now sits on my fireplace mantel, which still retains its original Maw & Co. tiles surrounding the firebox.

I purchased this 7-inch-tall vase at the Liberty & Co. department store in London in December, 2015. At the time, Liberty had a small section devoted to antiques, many of them from the English Arts & Crafts period. Maw & Co. was launched in 1850 and primarily produced high-end wall and floor decorative tiles. In the 1890s, they introduced a line of hand-painted art pottery, of which this is a beautiful example. The vase now sits on my fireplace mantel, which still retains its original Maw & Co. tiles surrounding the firebox.

Pyrography chair, submitted by Gail Tischler

This chair, with its burned wood design, sat in my aunt’s home in a corner. It was not useful—no one could sit on it as it was, and still is, fragile and wiggly. It was the graceful lotus design that caught my eye. Made by a lady friend, my aunt received it as a gift in 1907. The design is of lotus flowers on the front and a graceful crane on the back. I know now it is an example of pyrography, a term used in the early 1900s when heated metal tools were used to burn the designs. Pyrography kits for use in the home made the craft accessible to women who made items of beauty either for the home or to sell. The chair now sits on the landing of our stairway, and I enjoy it every day.