Small Home Gazette, Fall 2019

History of Linoleum Rugs

Conniving one material to imitate another is a great tradition in old houses, from manipulating paint into faux wood graining, or plaster into ersatz marble, to simulating the structural joinery found in many Craftsman-style Arts & Crafts houses. Yet for sheer practicality, not to mention amusement value, can there be any finer form of fakery than the linoleum rug? Imagine, all the visual loveliness of a woven carpet without the vacuuming, shampooing, and worrying about spills—just damp-mop and you’re done!

Although most of the linoleum sold up to the 1960s was probably installed wall-to-wall in kitchens, bathrooms, and public buildings, there was enough demand for rugs that every company’s catalog devoted a healthy batch of pages to them. Should you wonder if make-believe rugs are tacky today, have no fear. That’s what makes them so fabulous! Here’s what linoleum rugs and their look-alikes are all about and what to do if you find one in your old house.

Carpets for Mass Consumption

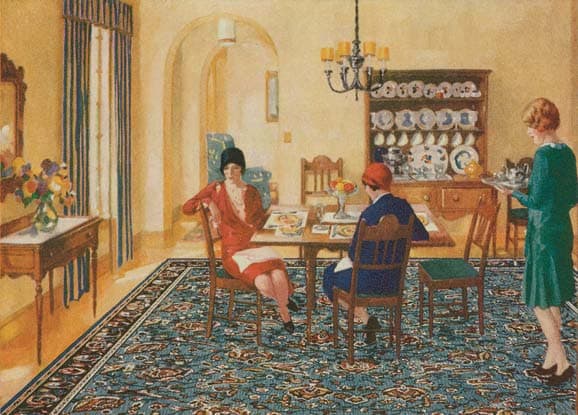

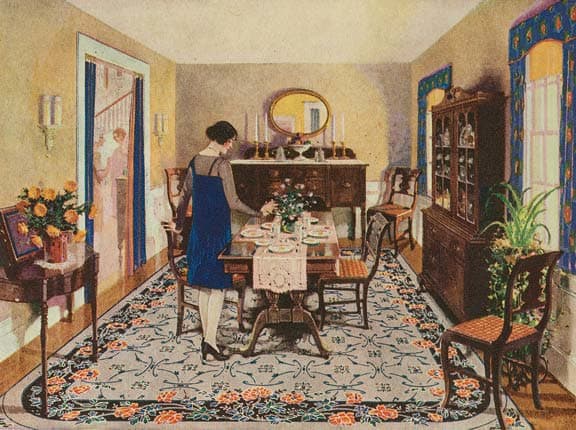

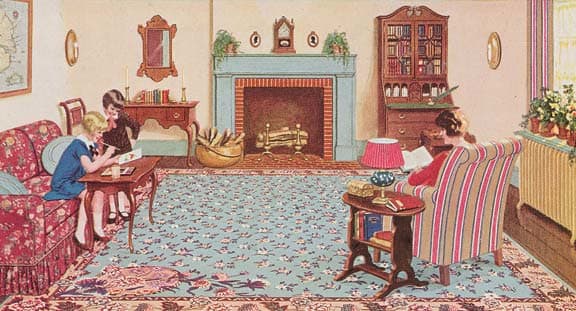

While linoleum manufacturers cornered the market in kitchens and baths with plain-Jane patterns, by 1929 competitors were invading living and dining rooms with colorful “rugs” that had never seen a loom and were not necessarily even linoleum.

What separates a linoleum rug from regular linoleum? Not much, beyond the fact that the typical rug is a movable rectangle with a border. Many manufacturers made the same patterns as both wall-to-wall products and rugs but the latter would also incorporate some sort of design around the edges. In addition, they tended to sell the rugs in standard rug sizes—4 by 6 feet, 5 by 7 feet, 6 by 9 feet, 8 by 9 feet, up to 12 by 15 feet. Rugs also came as mats (generally 2 by 3 feet) for placing in front of the sink. Beyond this, linoleum rugs don’t always have to look like textiles, and they don’t even have to be linoleum.

The evolution of the linoleum rug begins with the invention of linoleum by the Englishman Frederick Walton in 1863. Initially, linoleum came in solid colors, although soon after Walton debuted his wonder flooring, he developed marbleized, granite, and jaspé linoleum. By 1892, Walton had introduced two ways to make patterned linoleum: stencil inlaid and straight-line inlaid. Linoleum could also be decorated by hand-block printing with wood blocks—the same methods used to decorate floorcloths, the ancestors of linoleum—and this is the method primarily used to make linoleum rugs.

With a deft promotional spin, Congoleum made a virtue of rug patterns that were only paint-deep, promising “freedom from tiresome housework” because they could be “cleaned in a wink with a few strokes of a damp mop.”

In 1910, American linoleum producers suddenly faced a competing product that wasn’t linoleum at all. Called Congoleum, a contraction of Congo (the country that was a major source of asphalt) and linoleum, the flooring was an asphalt-saturated felt known generically as felt-base. When printed on the surface in oil paint with a linoleum-like design, felt-base looked just like linoleum, and it was cheaper than the real thing by a third. Initially, felt-base rugs were printed by hand using wood blocks in much the same fashion as printed linoleum, an expensive process. Only felt-base rug borders (generally printed to resemble wood flooring) were printed by machine. Within a couple years, though, the Congoleum Company decided to invest in a rotary press, and its first machine-printed rug came off the production line around 1913.

In 1927 Armstrong advertised its Genuine Cork Linoleum Rugs as a colorful flooring alternative for kitchens, be it this fanciful Japanese pattern or the standard grained look of jasper.

When felt-base was first introduced, linoleum manufacturers fought back, urging consumers to learn how to tell genuine linoleum: look for the woven burlap back. To add to the confusion, felt-base makers coated the back of their rugs with the same red iron oxide that linoleum manufacturers used on the back of linoleum. Nonetheless, the Armstrong Company, a leading linoleum producer, experimented with felt-base starting in 1916, producing Fiberlin rugs and flooring. In 1917 they introduced linoleum rugs, which sold so well they dropped the Fiberlin line in 1920. But a few years later they bought out the Waltona Company, another felt-base manufacturer, and began offering felt-base again in 1925. The Waltona line was renamed Quaker Rugs, and Armstrong stopped selling the real linoleum rugs after that.

Congoleum sold their rug product under the Gold Seal label. Other companies also got into the resilient rug business, both linoleum and felt-base, including Sloane, Blabon, Pabco, and Dominion (Canada). Some continued to offer both products even after the larger companies (Armstrong and Congoleum-Nairn) had stopped making linoleum rugs and only sold the felt-base merchandise. In general, by the late 1920s, most resilient flooring rugs were felt-base instead of linoleum. Felt-base rugs (and flooring) continued to be produced well into the 1950s.

A Plethora of Printed Patterns

Since these products were marketed as rugs, it’s no surprise they were often printed to resemble various kinds of woven or knotted carpets. Some even had printed fringe for full effect. The most amusing of these were based on traditional oriental rugs, though there were also fake braided rugs, rag rugs, and needlepoint rugs. Straw or other fiber matting was another fashionable motif—and easier to keep clean than the real thing!

Little more than borders and a floral pattern, such as this Chrysanthemum design, were necessary to turn functional flooring into a rug fit for a living room.

Florals of all sorts were popular from the 19th century up through the 1950s. Sometimes combined with florals or on their own, patterns that might be called ferns and fronds were fashionable, trying to resemble broadloom carpeting, perhaps. In the 1950s, tropical florals similar to the patterns found on bark-cloth draperies were offered by some companies.

At least as popular as florals were all sorts of geometric patterns, from tile-like compositions to designs that were termed jigsaw, random tile, and overshot interliners. Geometrics could either be printed as an all-over pattern, or on a background that vaguely resembled marble, clouds, or a pointillist painting. Many rugs also imitated the typical marble linoleum flooring with inlaid borders of solid color or contrasting marbleized colors. Patterns resembling wood were most often sold for use as rug borders, although rugs with patterns mimicking parquet were advertised for use in formal rooms (a bit of wishful thinking on the manufacturers’ part, perhaps). Though wood patterns always look fake to our eyes, don’t let it bother you; as with country wood-graining, embrace the fakeness.

Almost all manufacturers continued making rugs into the 1950s, running modern and atomic patterns in their catalogs right along with pages of ersatz originals.

During the 1930s and ‘40s, there were even a couple of full-on Art Deco/Moderne/Streamline rug patterns, though not as many as one might have liked to see. Similarly, in the 1950s there were a few designs that really screamed mid-century Modern. Nonetheless, the 1950s wasn’t really as modern as we think it was, and there were many more hokey florals and fake braided rugs than there were Space Age/ boomerang/kidney-shaped patterns. More’s the pity.

What are almost exclusively the province of linoleum or felt-base rugs, however, are patterns meant for kitchens or nurseries. Kitchen rugs featured vegetables and fruits, dishes, coffee and tea pots, chickens, fish, cows, and the like. Nursery rugs used motifs such as nursery rhyme characters, game boards, cute baby animals, cowboys, spaceships, maps, or the circus.

In their heyday, felt-base and linoleum rugs were most often used in bedrooms, covered porches, and attic living spaces. Sometimes they popped up in dining rooms, and you may uncover one while taking up wall-to-wall carpeting. If you’re very lucky, you may discover a never-used rug, still rolled up, stashed in the attic, basement, or garage. Or you may find rug sections lining the bottom of a closet or a drawer. These are pieces of history and shouldn’t just be tossed into the trash.

An old linoleum or felt-base rug is worth appreciating because it is unlikely this product will ever be made again. The few companies now producing real linoleum don’t offer patterns, let alone rugs, and no one makes felt-base flooring anymore. The closest you can get is a floorcloth, a pre-linoleum technology, these are usually custom-made and not cheap. So if you have a linoleum rug, treasure it, even if your friends don’t understand.

The late Jane Powell was a restoration contractor and author of a half-dozen books, including Linoleum and Bungalow Kitchens. This article, updated on January 23, 2019, is reprinted with permission of Old-House Journal (oldhouseonline.com). Images: James C. Massey archives.