Small Home Gazette, Fall 2020

Have a Jolly Halloween!

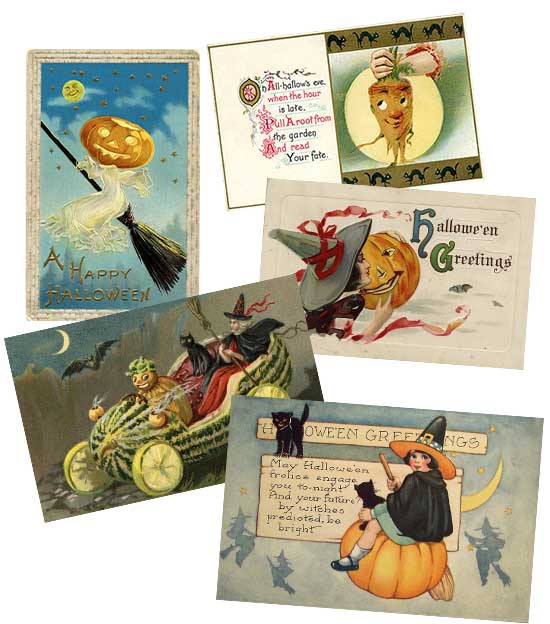

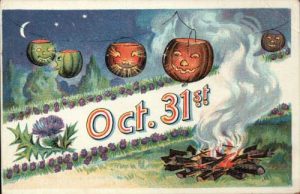

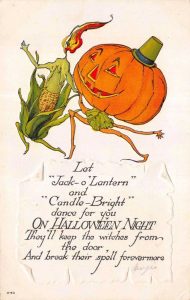

There is something disturbing about vintage Halloween postcards. Sure, there are plenty of black cats, owls, witches, moons and jack-o’-lanterns* but what about all those vegetables? Heads of cabbage dance; watermelons are cars; and corncobs fly to the moon. And children have carved pumpkins for heads.

Origins of Halloween

Halloween started with the ancient Celtic festival Samhain (a Gaelic word pronounced “sow-win”) to celebrate the end of the harvest season. Celebrated from October 31 to November 1, Samhain also marked the time of year when the barrier between the physical world and the spirit world broke down, allowing spirits to walk among mortals. Villagers joined with Druid priests to light a community fire to confuse these spirits.

Halloween started with the ancient Celtic festival Samhain (a Gaelic word pronounced “sow-win”) to celebrate the end of the harvest season. Celebrated from October 31 to November 1, Samhain also marked the time of year when the barrier between the physical world and the spirit world broke down, allowing spirits to walk among mortals. Villagers joined with Druid priests to light a community fire to confuse these spirits.

Trick-or-treating may have evolved from the ancient Irish and Scottish practice of “mumming” in the nights leading up to Samhain. People put on costumes and went door to door, singing songs to the dead. Cakes were given as payment.

Trick-or-treating may have evolved from the ancient Irish and Scottish practice of “mumming” in the nights leading up to Samhain. People put on costumes and went door to door, singing songs to the dead. Cakes were given as payment.

Enter the Middle Ages. Celebrations continued with community fires but bonfires at individual farms became a tradition to protect families from fairies and witches. Many Halloween traditions—wearing masks, telling ghost stories, and carving vegetables into lanterns—came from Samhain celebrations. Carved turnips attached to sticks and filled with hot coals were popular in Ireland.

As Christianity gained a foothold in pagan communities, church leaders attempted to reframe Samhain as a Christian celebration. In the 9th century, Pope Gregory declared November 1 as All Saints’ Day (to honor those believed to have gone to heaven) and November 2 as All Souls’ Day (to pray for those who died baptized but without having confessed their sins).

Neither of these Christian holidays replaced the pagan aspects of the celebration. October 31 became known as All Hallows Eve, or Hallowe’en (and eventually Halloween), continuing with much of the traditional pagan practices. In the 19th century, Irish immigrants brought these traditions with them to America.

Halloween Postcards

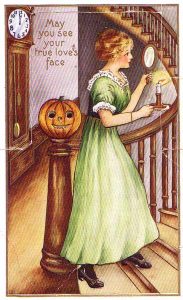

Halloween postcards became popular in the late 1800s. Courtship practices were a popular theme. Cards depicted a common belief that if a woman gazed into a mirror at midnight, the face of her future spouse would appear, and if she ascended a staircase holding the mirror, she would certainly see a face. This had to be done by candlelight, of course.

Halloween postcards became popular in the late 1800s. Courtship practices were a popular theme. Cards depicted a common belief that if a woman gazed into a mirror at midnight, the face of her future spouse would appear, and if she ascended a staircase holding the mirror, she would certainly see a face. This had to be done by candlelight, of course.

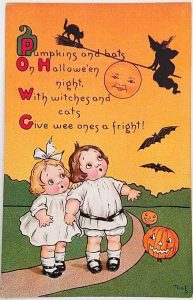

Other card designs depicted:

- Couples bobbing for apples. This game was a way to discretely get close to potential suitors.

- A rather strange ritual involving pulling a cabbage out of the soil. The shape of the roots suggested the look of a future spouse plus the taste of the cabbage suggested their temperament.

- Besides cabbages, squashes and pumpkins were popular—maybe a link to the autumnal harvest season of the past?

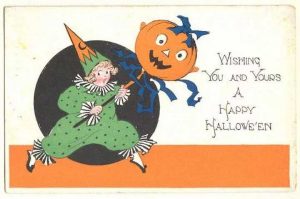

- Pumpkin-headed creatures—jack-o’-lanterns on the bodies of children, witches, and beautiful women.

- Witches, beautiful or otherwise, with black cats or bats or grinning jack-o’-lanterns.

- Beautiful women caressing a jack-o’-lantern.

- New inventions such as the automobile but with parts made of vegetables and fruits, and driven by a witch.

- The moon, black cats, goblins, ghosts, bats—the Halloween motifs we know so well.

Collectibles

Many of these postcards were illustrated by popular artists, printed by a few well-known card companies, and are now very collectible. The earlier, more elaborate cards were printed mainly in Germany but during WWI, importing would have been impossible as well as many card factories were destroyed. This meant more printing was done by American postcard manufacturers. These later cards have limited embossing and fewer colors, making them cheaper to produce and to sell.

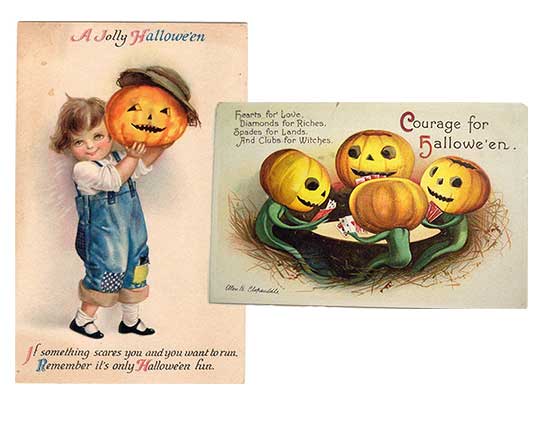

Two cards designed by Ellen Clapsaddle, 1910s.

Ellen Clapsaddle, was a freelance artist for the International Art Company. Her illustrations often featured small children. She is recognized as the most prolific American postcard and greeting card artist of her era, designing over 3,000 postcard illustrations during the heyday of souvenir postcards (1898 – 1915).

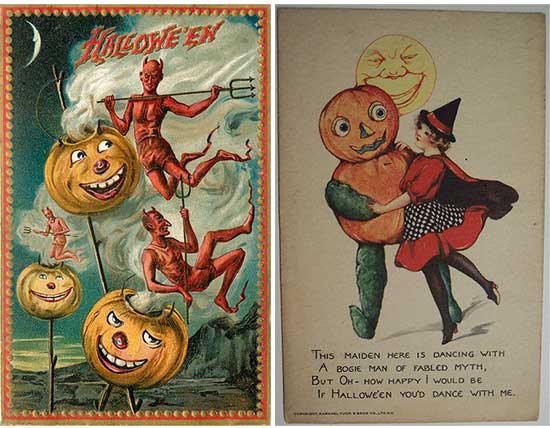

Two cards published by Raphael Tuck & Sons, Ltd.

Raphael Tuck & Sons was a business started in London in 1866, selling pictures and greeting cards, and eventually postcards, which became their most successful line. Their business was one of the best known in the “postcard boom” of the late 1800s and early 1900s. They entered the postcard market in the U.S. in 1900 with an office in New York. American artists designed many of the postcards, but the cards were printed in Europe (Germany, England) and then returned to the U.S. for sale.

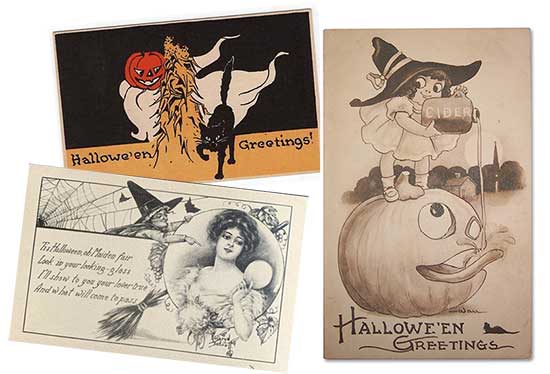

Published in 1910s by John O. Winsch; designed by Samuel J. Schmucker.

John O. Winsch, of Stapleton, New York, was a publisher of superior quality greeting postcards printed in Germany. He first issued postcards in 1910 and sold them at two for five cents when the common price was one cent each. The most collected of the Winsch postcards are the Halloween designs by American art nouveau artist, Samuel L. Schmucker.

Three cards printed by Gibson Art Company. Top left: Example of black cat series. Right: Designed by Bernhardt Wall. Bottom left: Printed in 1910s; designed by Kathryn Eliot.

Gibson Art Company printed a few postcards from 1907 to 1917. Many of the cards were printed in either sepia or black-and-white but their Halloween cat cards had orange backgrounds and others had pumpkin borders. Two of their well-known artists were Bernhardt Wall and Kathryn Elliot.

Sadly, the Depression ended the tradition of Halloween postcards, probably because people had little disposable income. But Halloween continues to thrive, mainly in the U.S. Our traditions are a mix of our immigration history; love for wearing costumes and for partying; and terror of all things spooky.

Sadly, the Depression ended the tradition of Halloween postcards, probably because people had little disposable income. But Halloween continues to thrive, mainly in the U.S. Our traditions are a mix of our immigration history; love for wearing costumes and for partying; and terror of all things spooky.

* A jack-o’-lantern is a carved pumpkin, turnip, or other root vegetable associated with Halloween. Its name comes from the phenomenon of a strange light flickering over peat bogs, called will-o’-the-wisp or jack-o’-lantern. The name is also tied to the Irish legend of Stingy Jack, a drunkard who bargained with Satan and was doomed to roam the Earth with only a hollowed turnip to light his way.

by Gail Tischler

by Gail Tischler