Small Home Gazette, Fall 2022

Up, Up and Away!

Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No, it is a giant dachshund! If you lived in New York City in November 1927, you might have seen this balloon creature floating high above—a remnant of Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.

Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No, it is a giant dachshund! If you lived in New York City in November 1927, you might have seen this balloon creature floating high above—a remnant of Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.

The first year of the parade was 1924. Known originally as Macy’s Christmas Parade, the store’s employees were dressed as clowns, cowboys, jesters and sword-wielding knights. They dodged between four marching bands; three floats pulled by horses; and elephants, camels, monkeys, bears and tigers, all on loan from the Central Park Zoo.

But there were no balloons.

Some sources attribute the idea for the first parade to Macy’s employees, many of whom emigrated to America from Europe and missed celebrations similar to the ones in their native countries.

Some sources attribute the idea for the first parade to Macy’s employees, many of whom emigrated to America from Europe and missed celebrations similar to the ones in their native countries.

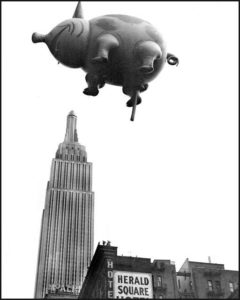

The real reason for its debut was to celebrate the expansion of Macy’s flagship store into what the company then claimed was “The World’s Largest Store.” The Manhattan Herald Square-based store occupied one million square feet and spanned a full block along 34th Street from Broadway to Seventh Avenue.

A tradition since the first parade, Santa rode in the last float and disembarked at Macy’s front door. From there, he unveiled the store’s holiday windows—each featuring animated marionettes designed by Tony Sarg, a Macy’s employee and puppeteer.

The Parade Is a Success…Sort of

The inaugural parade, while a modest production, attracted 10,000 spectators. Pleased with the response, Macy’s executives made plans to repeat it AND to improve it. The use of live animals came with a few problems. Some children were frightened by the animals’ closeness to the crowds, and street cleanup was a challenge.

A “Balloonatics” float in the 1926 parage inspired designer Tony Sarg to create the parade’s iconic character balloons.

And Tony Sarg, the creative force behind the parade, wanted to feature something that everyone, even those spectators standing way back, could see. The solution: balloons. Really, really big balloons. He turned to the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company in Akron, Ohio, for assistance.

The Balloons

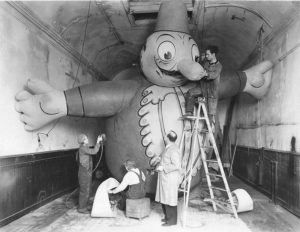

In 1927, the giant balloons, that are now the signature element of the parade, made their first appearance. Filled with oxygen, the rubberized silk balloons were propped up by teams of handlers, usually Macy’s employees. (Sarg thought of the balloons as upside-down marionettes.)

Cruder and smaller than today’s monster-sized balloons, the balloons still charmed the crowds. That first year, the cartoon character Felix the Cat was the most famous to debut. Felix was accompanied by a 60-foot dinosaur “attended by a bodyguard of prehistoric cavemen” as well as a 25-foot-long dachshund that “swayed along in the company of gigantic turkeys and chickens and ducks of heroic size,” to quote The New York Times.

Felix, the cartoon cat created in 1919, has the distinction of being the FIRST giant balloon ever made for the 1927 parade.

There was also a charming toy soldier; a 127-foot-long dragon propped up on stilts; and a 21-foot-long “human behemoth” (a mighty beast) carried on its back. All were designed by Sarg and produced by Goodyear.

Spectators were amazed when the “human behemoth” passed under Broadway’s elevated railroad on his back.

No one had given thought as to how to deflate or pack up the balloons after the parade. As a result, the balloon crew did what was easiest. They released them and watched the balloons drift skyward. The colder air of the atmosphere soon caused the air-filled balloons to pop as they rose, including Felix.

In 1928, Tony Sarg wanted bigger and better balloons. He decided to use a mixture of helium and air to fill the balloons, enabling designers to create even bigger balloons that would float along the parade route without propping them up.

Sarg also developed a time-release feature that created an opportunity for promoting the store. Crafted to leak slowly, the balloons would be set free, affixed with return address labels. Macy’s offered a $100 reward (about $1700 today) for the capture and return of any of the balloons.

The Fish and Tiger balloons were part of the 1929 parade, the first year that helium gas was used to send the puppets aloft.

It seemed like a good idea, but one balloon (the Tiger) landed on a roof in Long Island and caused a tug-of-war between neighbors. While pieces of the balloon were eventually returned to the store, there is no record as to whether anyone got the $100. Other helium balloons released that year had similar fates. The hummingbird was found broken in half and floating in the East River, pursued by two tugboats. A balloon called “the ghost” was last seen moving out to sea with a flock of gulls in pursuit.

In 1931, the balloons released included a 287-foot-long dragon. Imagine seeing that in the sky. And a blue hippopotamus balloon escaped the New York area and was reported to be “soaring somewhere over the ocean.”

Enter the Airplanes

The year 1931 was also the first balloon recovery that involved an airplane. Barnstorming aviator Colonel Clarence D. Chamberlin saw Felix and Jerry the Pig heading his way. With his passengers egging him on, he reached out of the open cockpit and lassoed the pig. The plane’s wing snared Felix but the cat got away, only to get caught in a high-tension wire in New Jersey where it burst into flames.

In 1932, student pilot Annette Gipson deliberately rammed her plane into a 60-foot tomcat balloon released after the parade. The plane’s left wing got caught in the balloon fabric and sent the plane plummeting. Although her instructor gained control of the aircraft and landed it safely, the yellow-striped balloon was reduced to tatters. That was the last year the character balloons were set free.

Weather and Other Challenges

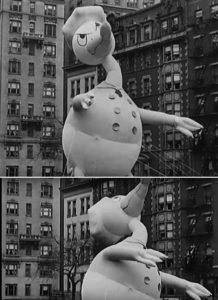

Weather has always been a challenge for the balloons. In the 1930s, Macy’s had an emergency crew that could do surgical repairs mid-parade. Sometimes a damaged balloon could be patched; filled with more helium; and sent on its way. Many times, the wind had blown a balloon into a sign or a tree. On occasion, this knocked debris into the crowds, injuring people.

Typical accidents in the early years involved balloons being torn in half after hitting electric signs or losing a tail or nose after a puncture. Balloons that split had to be removed but punctures were repaired enroute. Sixteen incidents have occurred since 1927, beginning with that first Felix flying high and popping.

Gobble the Turkey made his debut in 1929, gobbling and wobbling his way down the parade route. Handlers struggled to keep Gobble in line as gusty winds tossed the balloon, but its chest was punctured by a “No Parking” sign.

An early version of Donald Duck debuted in 1935 and brought about another surprise. His long, skinny neck whipped his head about in the wind, causing the rain water that had collected in his hat to dump all over bystanders.

As the balloons became more sophisticated, the crew handling each balloon needed training. Today, every balloon’s crew includes a pilot, who navigates the route by walking at the head of the crew. The pilot monitors the wind and can issue orders to the handlers to control the balloon—or even deflate it—should it pose a risk to parade-goers. A pilot must be able to walk the entire 2.5-mile route backward, without stumbling.

In its almost 100 years of delighting people, not rain or snow, below freezing temperatures, blustery winds, the Great Depression, or COVID have caused the cancellation of the parade. The exceptions were the years 1942 to 1944 because of WWII. For its part, Macy’s donated 650 pounds of rubber to the U.S. military that would otherwise have been used in balloons.

For many, the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade has become synonymous with eating a turkey dinner. Televised first in 1945 by NBC, balloon lovers can now livestream the parade on Twitter and YouTube.