Small Home Gazette, Spring 2017

Golf in the Bungalow Era

Or, Greene and Greene and Greens

Dedicated to the memory of my dad, who enjoyed golfing before he had nine kids.

One in five Minnesotans play golf every year—that’s more people per capita than in any other state. The game’s popularity here originated with the first round played in 1893, in a St. Paul cow pasture with tomato cans for holes and fishing poles as flags. Deemed “a silly game which could not possibly last,” it took until 1898 for the Town & Country Club of St. Paul to open a course. The Minikahda Club built its first course in 1899 with nine holes overlooking Lake Calhoun. In 1916, the first public golf course opened in Minneapolis at Glenwood (Theodore Wirth) Park, where residents could play the nine holes for free on a sand course. In less than 10 years, the park board operated four 18-hole courses and was preparing to add a fifth at Lake Hiawatha.

Modern machinery and the economic boom of the 1920s propelled the game of golf into full swing. With more free time and money for leisure activities, weekend golfers doubled to one-half million between 1916 and 1920. By the end of the decade, an estimated 3 million golfers were playing in the United States on over 4,000 golf courses. Miniature golf also swept the nation. Those who couldn’t afford the costs of equipment and club memberships could enjoy a much cheaper version of the sport at one of more than 30,000 mini-golf venues.

Build It and They Will Come

The guidance about greens development offered by authors Wethered and Simpson in The Architectural Side of Golf (1929) still holds true today—“Designers should not fail in any of the obvious points for building courses: every hole should be interesting; the maximum variety of holes allowed by the site should be provided; the natural beauty of the country should be impaired as little as possible; a premium should be put on good golf; and the course should be equally interesting and amusing to the first-rate and the second-rate golfer.” When I read this advice, parallels to the principles of the Arts & Crafts movement jumped out at me: finding pleasure in work and craftsmanship; valuing nature; and being accessible to ordinary people.

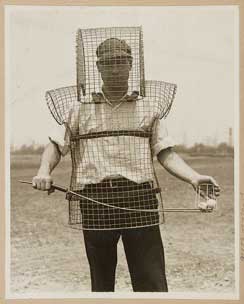

Caddy Mozart Johnson wearing “the latest safety device for golf courses” fashioned from wire-mesh and worn over the head and upper torso to protect “caddies and ball-retrievers from wild golf balls.” Photo from the Library of Congress archives.

I’m not the first to note this shared aesthetic. I came across a five-part series on Arts and Crafts Golf by Thomas MacWood of Columbus, Ohio. He details the simultaneous rise and interconnectedness of course design and the Arts & Crafts movement. MacWood notes how various golf course architects reflect the ideals of simplicity; variety; harmony of man-made and the environment; reverence for the past; the inherent virtue of nature; and individualism. He even mentions Greene and Greene while writing about the greens. The movement influenced the architecture of buildings, as well as greens. Several of the golf clubhouses you can visit today across the country were built in the Arts & Crafts style. Alas, just as many of these beautiful buildings are now found only in faded photographs.

Resources

If it is raining, and you can’t get out on the greens, enjoy these resources:

- Arts and Crafts Golf, by Thomas MacWood, Golf Club Atlas

tinyurl.com/n5qly8r

- “100 Years of Minnesota Golf”

tinyurl.com/lx5htlz

- “Bobby Jones: How I Play Golf,” the first great American golfer instructs James Cagney and others in this 11-minute video (1931, 1933).

tinyurl.com/m8who53

- “1920s Miniature Golf Craze,” 1-minute video

tinyurl.com/kwehhet