Small Home Gazette, Spring 2019

Now Join Hands…

A Look at Weddings During the Bungalow Era

“There seem to be a hundred and one important details to be considered in preparing for a wedding.”

This quote is from the chapter on “Weddings” from The White House Book of Etiquette, published in 1903. It’s the kind of statement that could apply to weddings of any era—including today’s. But those details have changed over time. Let us look at a few of yesteryear’s interesting traditions.

When to Marry?

In the Arts & Crafts era, the privilege of “naming the day” belonged to the bride-to-be (and her mother). Traditional weddings were on weekdays. A popular rhyme guided their choice:

Monday for wealth,

Tuesday for health,

Wednesday best day of all,

Thursday for losses,

Friday for crosses,

Saturday no luck at all.

Weddings on Sunday were not customary; nor were evening weddings. Today, in defiance of the rhyme, Saturday afternoons or evenings are the most popular choice for a ceremony.

“High noon” was considered a fashionable time in the early 1900s but, for many, an afternoon wedding was more convenient. The mid-day ceremony typically involved an elaborate breakfast (really a sit-down lunch), while an afternoon wedding was followed by a simpler reception.

For many couples, the wedding took place at home with only a few family members and friends present. No procession was expected. The couple entered the room and faced the wedding official together. Refreshments were served, but few families hosted an elegant meal.

The Dress

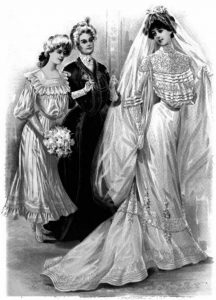

What a bride and her attendant wore in 1902.

Just as today, bungalow era brides dressed in their best. High society brides were outfitted at the height of fashion, sparing no expense, while those of limited means dressed as nicely as their budgets allowed.

In the early 1900s, the customary wedding dress featured an S-shaped corset, which drew in the stomach and pushed out the bosom, an effect emphasized by frills on the bodice. “Gigot” sleeves were popular—wide, puffy sleeves that tapered to a narrow forearm.

While white was the color of choice for affluent brides (due to Queen Victoria’s trend-setting white gown in 1840), other brides chose to wear azure, mauve, or pale pink. Small waists, high collars, long trains, long gloves, and veiled hats also were in fashion.

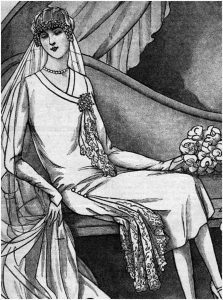

A bride and her attendant in 1916.

The 1910s introduced a more flowing silhouette for wedding gowns, sometimes with a train. Waistlines were higher, and sleeves ended at the elbows. Dancing became a popular part of the wedding celebration, often with phonographs providing the music. The looser silhouette allowed the bride to enjoy the dancing.

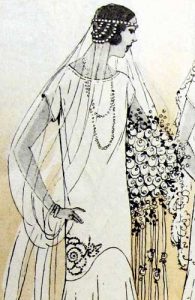

A bride’s dress for the flapper era. Her bouquet is a “composite” style—one giant bloom, created from individual petals.

Enter the 1920s Jazz Age. Waistlines and necklines dropped, and a more streamlined silhouette took hold. Expensive gowns featured ornate beading and embroidery, while bouquets were larger than life. Brides favored Juliet headdresses (a cap made of open weave fabric which fit snugly on top of the head, decorated with pearls or semi-precious stones) or cloche hats for their veils.

Some weddings in the 1920s dispensed with traditional ceremonies. This couple has just left city hall.

The rise of the flapper also led to more informal weddings—elopements and city hall marriages were not uncommon. In classic flapper fashion, these brides wore dresses with hems raised to the knee paired with a short, curled bob haircut, and a headdress without a veil.

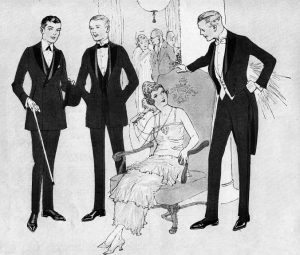

Tuxedo styles from 1919.

How about the groom? At the turn of the century, proper gentlemen’s wedding attire consisted of a frock coat, striped trousers, and a light waistcoat. The morning coat or cutaway regained popularity by 1910 and was still in widespread use after WWI. Working men wore a dark suit, which eventually gave way in the 1930s to a formal suit, or tuxedo, often rented for the occasion.

The Ring

The exchanging of rings is one of the oldest marital traditions around, beginning with a grass ring for the bride in prehistoric times. The ancient Romans placed a ring on the third finger of the left hand because they believed its vein ran directly to the heart. And why a ring? Because it is circular, symbolizing never-ending love.

Spending significant money on rings is not a long-standing tradition. In the early 1900s, a standard wedding ring was a simple band of gold. The 1909 Sears Catalog, for example, had pages of rings with pearls, rubies, sapphires and diamonds for ladies, but none were designated as engagement or wedding rings. Many couples put their money toward their honeymoons and post-wedding residences.

A 1927 magazine ad promoting jewelers, stating: “Her engagement ring…a symbol of her pride in you.”

It wasn’t until 1930, when the De Beers Company discovered new mines, that diamond rings became affordable and more widespread.

As for the groom, it wasn’t until WWII that a male wedding band became common. Married men who fought in that war wore a wedding ring throughout their deployment to remind them of their families at home.

The Flowers

A 1920s bride wearing a cloche hat. She is carrying a “sheaf” bouquet of blossoms with long stems.

Bungalow brides carried bouquets filled with white roses, orange blossoms, lilies of the valley, orchids or daisies, which came in several styles.

The sheaf was a collection of blossoms with long, full stems, first fashionable in the early 1900s. It was meant to be cradled along one bent arm.

A 1925 magazine illustration of a wedding dress. Note the cascade bouquet.

Cascades were all the rage in the 1910s and ‘20s, expanding from posy-size, with trailing ribbons and vines, to an immense and impressive size.

Example of a composite bridal bouquet.

The composite first appeared early in the 20th century. It was a single giant bloom constructed by hand from individual flower petals to resemble one oversized flower. It was mostly used by brides with an unlimited budget.

Wedding Cake

Starting in the 1900s, tiered, entirely edible, white wedding cakes were traditional. In the 1910s, cakes were simple, with a single white tier topped with fresh white flowers. The trend in the ‘20s was for the biggest, tallest, most ornate cake possible. The use of supporting pillars (wooden sticks covered in icing) between the wedding cake tiers helped add height.

Starting in the 1900s, tiered, entirely edible, white wedding cakes were traditional. In the 1910s, cakes were simple, with a single white tier topped with fresh white flowers. The trend in the ‘20s was for the biggest, tallest, most ornate cake possible. The use of supporting pillars (wooden sticks covered in icing) between the wedding cake tiers helped add height.

But not all wedding cakes were white towers—see an authentic but unusual cake recipe at end of this article.

Wedding Gifts

A 1922 booklet cover for Stieff’s silver.

Wedding gifts are an evolution of two ancient traditions. A “bride price” was once paid to the bride’s family by the groom’s family—typically land and animals—to show his ability to provide for a wife. A “dowry” was the wealth provided by the woman’s family at the time of the marriage to help start the new household. Because of this exchange of material goods, guests to the ceremony did not bring gifts.

Gift giving, as we know it, began in 1924 when Marshall Field’s, now called Macy’s, introduced the wedding gift registry, and other stores were not far behind. The gift-giving tradition was aimed at helping young couples get started in their new home.

The Honeymoon

The idea of a honeymoon dates back to the 5th century when moon cycles dictated calendar time. Back then, a newlywed couple drank mead (a honey-based alcoholic drink) during their first moon of marriage.

The origin of the word itself comes from the Old English “hony moone.” Hony, a reference to honey, refers to how sweet the new marriage is. Moone refers to the fleeting amount of time that sweetness would last.

In a glossographia, or dictionary, written by Thomas Blount in the 1600s, “honeymoon” was defined as: “Married persons love well at first, and decline in affection afterwards: It is honey now, but will change as the moon.”

Couples in 19th century Britain used their honeymoon to go on a bridal tour to visit friends and family who could not attend the wedding ceremony.

Newlyweds in the early 1900s were presented with a range of honeymoon options that would give them some time alone. The groom typically selected the location and paid for the trip. While some couples stayed at a seaside resort, others camped, canoed, or took bicycle tours.

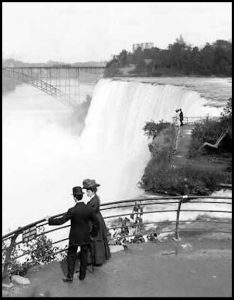

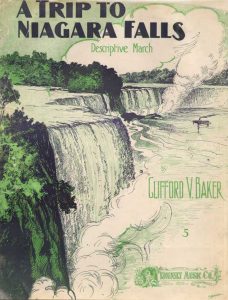

The cover of a piece of sheet music published in 1905. Over time, certain destinations became synonomous with honeymoons.

Gradually the meaning of “honeymoon” became connected to the destination itself such as Niagara Falls, promoted as the “Honeymoon Capital of the World.” With the opening of the Erie Canal; the building of railways; and then the invention of the automobile, Niagara Falls became accessible to more people.

In summary, weddings have always been guided by etiquette and traditions, and not just for those of social standing. Over time, many have been continued or transformed into today’s wedding customs. Couples today place an emphasis on personalization plus creating a great guest experience. One thing has not changed—the wedding of today still involves “one hundred and one important details.”

Today, we think of wedding cakes as light in consistency, though a buttercream frosting might add heft to the overall confection. Below is an early 20th century recipe that looks like it would produce something more akin to a holiday fruitcake.

Wedding Cake Recipe (1911)

Ingredients

1 pound of brown sugar

1 pound of butter

1-1/2 pounds of pastry flour

12 eggs

1 pound currants, picked over, washed, and rolled in flour

2 pounds of raisins, seeded

1/2 pound of citron, cut thin

1/2 pound of figs, chopped

1 pound of almonds, blanched and chopped

1 glass of nice jelly

1 wine glass of grape juice

1 teaspoonful of extract of cinnamon

1 teaspoonful of ground cloves

2 teaspoonfuls of grated nutmeg

Directions

- Cream the butter and sugar together, and mix ingredients in the usual way, having the whites and yolks of the eggs beaten separately, and folding in the stiffly beaten whites the last thing, after adding the grape juice. Beat up the ingredients perfectly smooth before folding in the eggs.

- Bake in two loaves for two hours or longer if necessary to cook through. This will keep a long time, and should be baked in a moderate oven, with no jarring of the stove. Test with a broom straw.

Note: No soda or baking powder is used, as the eggs do the raising.

by Gail Tischler

by Gail Tischler