Small Home Gazette, Spring 2019

Tractor City

A cast iron tractor seat hangs from the picture rail in my bungalow’s living room. Its ventilation cutouts radiate like a sunrise from the “Minneapolis-Moline” labeled core—a once-functional work of art created by industrial designers now simply functions as art. My quest for a 1920s Moline tractor seat began after discovering some of my neighborhood’s history.

A cast iron tractor seat hangs from the picture rail in my bungalow’s living room. Its ventilation cutouts radiate like a sunrise from the “Minneapolis-Moline” labeled core—a once-functional work of art created by industrial designers now simply functions as art. My quest for a 1920s Moline tractor seat began after discovering some of my neighborhood’s history.

Raised in the suburbs and now living in the city, my interest in tractors is centered a mile from my home. At the corner of Lake Street and Minnehaha Avenue, where a Target store and other businesses now stand, the Minneapolis-Moline Company once occupied 26 acres of land and provided jobs that supported local working class families living in the Hiawatha-Lake Street bungalow-filled neighborhoods.

The Twin Cities were a pivotal force for increasing U.S. agricultural production. Minneapolis’ history as “Mill City” is well known—the Mississippi River’s St. Anthony Falls once powered up to 20 stone flour mills. The same rail lines that brought wheat east from the prairies, shipped west the Minnesota-made tractors used to cultivate it. Since 1905, 112 different tractor-manufacturing firms have started in Minnesota—more than any other state. Industrial Ohio is a distant second with 81, and agricultural Wisconsin hosted a mere 60.

The Twin Cities were a pivotal force for increasing U.S. agricultural production. Minneapolis’ history as “Mill City” is well known—the Mississippi River’s St. Anthony Falls once powered up to 20 stone flour mills. The same rail lines that brought wheat east from the prairies, shipped west the Minnesota-made tractors used to cultivate it. Since 1905, 112 different tractor-manufacturing firms have started in Minnesota—more than any other state. Industrial Ohio is a distant second with 81, and agricultural Wisconsin hosted a mere 60.

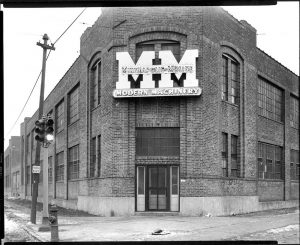

The main entrance of the Minneapolis-Moline production facility, formerly located at the intersection of Lake Street and Minnehaha Avenue in Minneapolis. Image used with permission of the Minnesota Historical Society.

New agricultural technology often debuted at the Minnesota State Fair. The 1860 fair was the first to feature a display of farm implements. Machinery Hill grew to 80 acres over time, occupying one-third of the fairgrounds. It featured 100 manufacturers, including Minneapolis-Moline, which had a permanent building. Early state fairs often featured reaper trials and plowing matches that demonstrated the potential of new farm equipment.

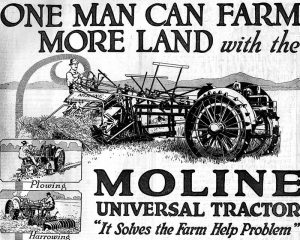

Minneapolis-Moline was formed in 1929 by a merger of Minneapolis Steel & Machinery; Minneapolis Threshing Machine Company; and Moline Plow Company. Headquartered in Hopkins, production sites included Minneapolis’ Lake Street and Como Avenue plants and one in Moline, Illinois. According to local lore, Highway 7 was built to facilitate getting workers between Hopkins and the plant on Lake Street in Minneapolis. While Minneapolis was never nicknamed “Tractor City,” the Minneapolis-Moline Company was American’s fifth largest farm machinery producer.

Minneapolis-Moline was formed in 1929 by a merger of Minneapolis Steel & Machinery; Minneapolis Threshing Machine Company; and Moline Plow Company. Headquartered in Hopkins, production sites included Minneapolis’ Lake Street and Como Avenue plants and one in Moline, Illinois. According to local lore, Highway 7 was built to facilitate getting workers between Hopkins and the plant on Lake Street in Minneapolis. While Minneapolis was never nicknamed “Tractor City,” the Minneapolis-Moline Company was American’s fifth largest farm machinery producer.

The Comfortractor—part tractor, part automobile.

Minneapolis-Moline’s Twin City tractor line was highly successful, innovating new models for decades. The company even pioneered enclosed cabs, now a tractor standard, with its Comfortractor in 1938. This hybrid vehicle combined the utility of a tractor and the comfort of an automobile. It was intended to be worked on the farm; then washed and used for a weekend drive into town. Though the $1,900 Comfortractor was a financial flop at the time, restored specimens today sell for as much as $135,000.

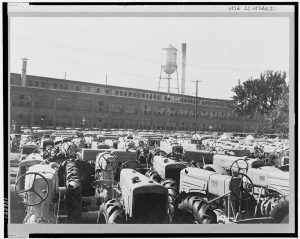

Freshly minted Minneapolis-Moline tractors, ready for distribution. Image courtesy of Library of Congress.

The last Moline tractor rolled off the line in 1972. The company’s modern tractors were so well executed that many of these machines are still working on farms all over the world.

One of several Minneapolis-Moline tractors on display at “The Moline” apartment complex in Hopkins.

You can find remnants of our past tractor power around the cities. The State Fair’s once mighty Machinery Hill has dwindled to the block long “Old Iron Show,” where you can see antique farm equipment with free demonstrations and displays. In Hopkins, “The Moline” is a luxury apartment complex sited where the former headquarters of the Minneapolis-Moline tractor company stood. Its first floor lobby features an antique tractor display that is open to the public.

The TractorWorks Building in the Minneapolis North Loop neighborhood used to be a John Deere tractor factory. And stop number 16 of The Museum in the Streets “27th and Lake: Industry and Transportation Infrastructure” walking tour honors my neighborhood’s long gone tractor factory.

Resources

“It’s a tractor! It’s a car! No, it’s the Comfortractor!”

“It’s a tractor! It’s a car! No, it’s the Comfortractor!”

tinyurl.com/y4svbeur

The Museum in the Streets walking tour map

tinyurl.com/y5awt3fj

“Titans of the tractor trade”

Pioneer Press, August 22, 2009

tinyurl.com/y23hzkvm