Small Home Gazette, Spring 2022

Dance ‘Til You Drop

Dance marathons were one of the early 1920s giddy, jazz-age fads testing human endurance. Alma Cummings, a dance instructor, may have started it all in the U.S. in 1923 when she danced for 27 hours with six different partners, ending with an audience-pleasing waltz. This feat took place in New York City and inspired dance studios and promoters around the country to start staging dance marathons.

Dance marathons were one of the early 1920s giddy, jazz-age fads testing human endurance. Alma Cummings, a dance instructor, may have started it all in the U.S. in 1923 when she danced for 27 hours with six different partners, ending with an audience-pleasing waltz. This feat took place in New York City and inspired dance studios and promoters around the country to start staging dance marathons.

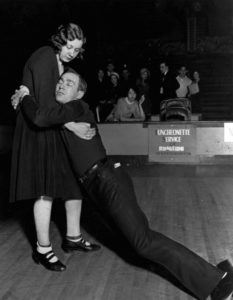

While Cummings’ feat was impressive, audiences cared little about technique and more about the stamina of dancers. Contests of human endurance and desperation, couples danced almost non-stop for hundreds of hours (as long as a month or more), competing for prize money. Outside of scheduled rest breaks, if either partner stopped moving or touched a knee to the ground, the couple was eliminated. Last couple standing won the prize.

Bunion Derbies

Casually called “bunion derbies” and “corn and callus carnivals,” promoters preferred the label “walkathons.” This was still a time of persistent religious beliefs that dancing was sinful, and “walkathon” was a less threatening name.

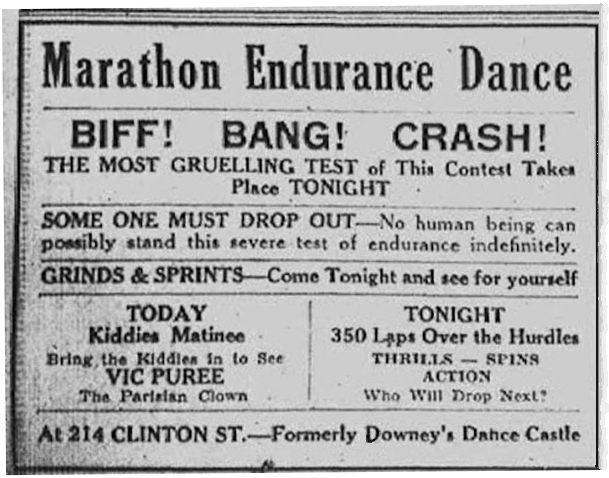

Dance marathons were both genuine endurance contests and staged performance events, with professional entertainers mixed in with hopeful amateurs. Promoters looked for “virgin spots” to stage an event—towns unexposed to dishonest promoters who often skipped town without paying bills. They looked for local sponsors such as the Veterans of Foreign Wars or the American Legion to lend an air of respectability. Extensive advertising was used to draw in crowds.

Dance marathons were both genuine endurance contests and staged performance events, with professional entertainers mixed in with hopeful amateurs. Promoters looked for “virgin spots” to stage an event—towns unexposed to dishonest promoters who often skipped town without paying bills. They looked for local sponsors such as the Veterans of Foreign Wars or the American Legion to lend an air of respectability. Extensive advertising was used to draw in crowds.

Movie theater owners, who lost money when their patrons chose a marathon over a movie, were chief opponents. And churches and women’s groups objected on the moral grounds of full body touching as well as charging for the privilege of watching people being degraded.

The Show Must Go On

An admission price, usually 25 cents, entitled audience members to watch this combination of vaudevillian antics and a grueling struggle of constant moving—pushing through exhaustion; hunger; bunions; shin splints; and elimination events like sprints and removal of rest periods.

An admission price, usually 25 cents, entitled audience members to watch this combination of vaudevillian antics and a grueling struggle of constant moving—pushing through exhaustion; hunger; bunions; shin splints; and elimination events like sprints and removal of rest periods.

Attendance was heaviest during evening hours, and contestants were expected to actually dance to a live band. Phonograph records were played during the day.

Couples were required to remain in motion for 45 minutes each hour, with 15 minutes allowed for rest. When the air horn blew, dancers left the floor for rest areas filled with cots. Sleep was usually immediate. After 11 minutes, the horn sounded again. Female dancers were revived with smelling salts; males were often splashed with ice water.

Medical services were available, and dancers were commonly treated for blisters, sprains and swollen feet in full view of the audience. A collapsed dancer was disqualified. The more a marathon event allowed the audience to see the dancers’ emotions, the larger crowd it attracted.

Medical services were available, and dancers were commonly treated for blisters, sprains and swollen feet in full view of the audience. A collapsed dancer was disqualified. The more a marathon event allowed the audience to see the dancers’ emotions, the larger crowd it attracted.

Most promoters fed contestants 12 times a day. Couples did a shuffling dance motion while standing next to a chest-high table to eat meals of oatmeal, eggs, toast, oranges and milk.

Usually, only the top three couples finishing won any money. To promoters, a successful dance marathon made money and resulted in no arrests. To dancers, a successful marathon meant a cash prize, and as the years got closer to the Great Depression, it meant being fed and sheltered for the length of the contest.

Minnesota Marathons

The year 1928 was a popular year for dance marathons, not only in places like New York’s Madison Square Garden, but here in Minnesota. It seems likely Twin Cities bungalow owners participated, either as spectators or dancers.

- An Endurance Dance was put on by the Veterans Association at the Kenwood Armory, starting June 18, 1928. In all, about 140,000 people watched this two-week long marathon. The winning couple won $1000, and the event took in $100,000 in admission fees. The Minneapolis Star newspaper referred to the event as “freak amusement” and went on to say “People are pretty free with their money and not particularly squeamish about the quality of their recreation.”

- The Bearcat Dance Marathon took place again at the Kenwood Armory, starting September 5, 1928. It lasted 104 hours.

- An All-Minnesota Dance Marathon was held in 1928 at the Coliseum Ballroom in St. Paul.

Minnesota Boy Makes Good

Callum deVillier was born in 1907 in Lanesboro, Minnesota. In his 20s, he competed in, and won, 12 dance marathons across the U.S. He set his first world record in 1928 at the Kenwood Armory in Minneapolis. He later set his final world record for dancing 3,780 hours in Somerville, Massachusetts, in 1933. This amounted to over five months of continuous dancing.

Callum deVillier was born in 1907 in Lanesboro, Minnesota. In his 20s, he competed in, and won, 12 dance marathons across the U.S. He set his first world record in 1928 at the Kenwood Armory in Minneapolis. He later set his final world record for dancing 3,780 hours in Somerville, Massachusetts, in 1933. This amounted to over five months of continuous dancing.

Following the Somerville Marathon, he married his dance partner, Vonnie Kuchinski. They danced in a few more marathons and had nightclub appearances across the country. The marriage did not last. DeVillier went on to run a hair salon in St. Louis Park. It seems his big feat in Massachusetts was his last, but his headstone in Lakewood Cemetery, Minneapolis, proudly states: “World Champion Marathon Dancer 3780 Continuous Hours.”

All Things Must End

The craze hit its peak during the Depression when audiences were looking for cheap entertainment, and an excess of people desperate for some quick cash provided a steady supply of contestants for the events. Promoters had taken what started as a fun, stunt-like, 1920s curiosity and turned it into a business for a country shifting into hard times.

The craze hit its peak during the Depression when audiences were looking for cheap entertainment, and an excess of people desperate for some quick cash provided a steady supply of contestants for the events. Promoters had taken what started as a fun, stunt-like, 1920s curiosity and turned it into a business for a country shifting into hard times.

The popularity of dance marathons began to dwindle as the novelty wore off; “professional” marathoners started popping up more and more; and “virgin towns” started becoming scarce. By 1935, 24 states had banned dance marathons. The late 1930s saw an end to these events.

Dance marathons of today inflict less pain; usually last one day; and serve to raise money for a charity. For example, this year’s ‘Sota Thon took place on March 19, 2022, in Coffman Union, Minneapolis Campus. This annual event is sponsored by Dance Marathon at the University of Minnesota, a student philanthropic organization with a mission to raise awareness and support for Gillette Children’s Specialty Healthcare in St. Paul. ‘Sota Thon is an eight-hour celebration of dancing and games involving fundraisers and the children they help.

Dance marathons of today inflict less pain; usually last one day; and serve to raise money for a charity. For example, this year’s ‘Sota Thon took place on March 19, 2022, in Coffman Union, Minneapolis Campus. This annual event is sponsored by Dance Marathon at the University of Minnesota, a student philanthropic organization with a mission to raise awareness and support for Gillette Children’s Specialty Healthcare in St. Paul. ‘Sota Thon is an eight-hour celebration of dancing and games involving fundraisers and the children they help.