Small Home Gazette, Summer 2013

Power in the Bungalow Kitchen

We were lucky in the wake of the June 28 storm with 70-mile-an-hour straight-line winds. The only damage our house sustained was wax drippings on the floor from candles and a questionable half-pound of hamburger, which we tossed. Neighbors lost trees, some had damage to their homes, and one had their car’s roof crushed under the weight of the boulevard ash.

We were lucky in the wake of the June 28 storm with 70-mile-an-hour straight-line winds. The only damage our house sustained was wax drippings on the floor from candles and a questionable half-pound of hamburger, which we tossed. Neighbors lost trees, some had damage to their homes, and one had their car’s roof crushed under the weight of the boulevard ash.

This wasn’t the first time we’ve lost power. Last December our refrigerator died two days before Christmas. We were able to use our back porch as a walk-in freezer and use large bowls packed with snow to keep perishables cold until we had time to shop for a replacement. Without the good fortune of Minnesota’s cold winter this June, I began the countdown clock against the Minnesota Department of Health’s warning that foods that lose refrigeration for more than four hours can pose a risk of illness.

During our 13 hours without power following the storm, I thought a good deal about the benefits of electricity, especially about its benefits in the kitchen.

Built in 1924, my home has always been electrified. Lights have usually come on at the flick of a switch. Perishable food has been kept fresh and safe for consumption for days on end. Convenience and sanitation in the kitchen were major themes during the bungalow era, and books and magazines endlessly touted improving the kitchen’s efficiency and cleanliness.

Sanitation

Back then, germs were a big health concern, even though the kitchen had been converted from being a place of animal slaughtering and industry (candle and rag-rug making, for example) to one of cooking and storage. Advertisers in the rapidly growing pre-packaged foods industry used concerns about germs to tout their wares, such as a 1920s ad for Ralston whole wheat hot cereal that read, “When Pandora opened the box and let loose all the ills, she did no more than many a housewife is unwittingly doing three times a day.” That’s a line that would certainly motivate me to order pizza rather than risk the ills I might cook up in the kitchen.

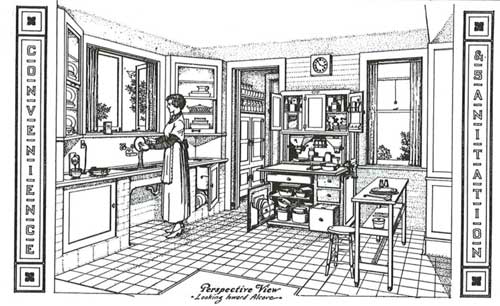

Note the electric mixer on the counter at the far left of the image.

The homemaker was warned about the need to keep her kitchen clean. “Every housekeeper knows, in theory, the dangers hanging over her family in case the refrigerator is not kept immaculate; yet as a matter of fact, it is very easy to allow a few days to go by without giving it the proper care, and she is appalled at the results she finds,” according to Keith’s Magazine (May 1921). Fortunately, ladies were given hope for a better tomorrow. “The kitchen of the future is going to be very much like the operating room of a hospital, being furnished with materials and equipment that are absolutely clean and sterile.” Although our new kitchen fridge is stainless steel, my cooking and cleaning habits make it far from sterile.

Convenience

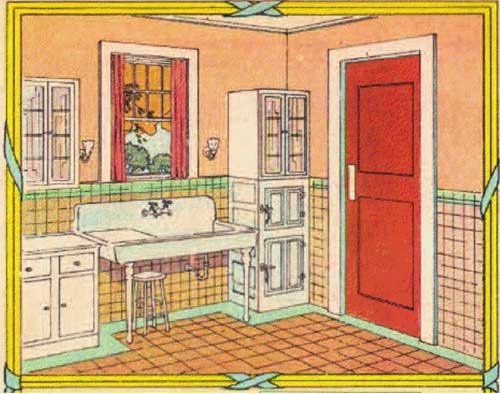

The introduction of electricity into neighborhoods radically altered the kitchen, allowing for lights and fans. Ice boxes kept food fresh much longer than Victorian root cellars. Heating systems and hot water sources changed space requirements in the kitchen. Tanks gave a flow of hot water on demand, rather than the need to heat water on a stove.

Coal ranges were becoming obsolete. Gas stoves became popular in the 1880s, as gas lines were more widespread. Gas ovens with top burners were found in most households by the 1920s. Electric stoves, developed in the 1890s, did not begin to catch on until the late 1920s when electricity began to be more widely supplied to private homes.

Before electric refrigeration, cellars and ice boxes were the only means of keeping fresh perishables. The best iceboxes were made with rear or end doors to allow icing from the outside. This not only kept the iceman from tracking in dirt, but it made refrigeration available in northern climates six months of the year without ice. The cold air from the outside produced the refrigeration. For the average family, a refrigerator of 65 pound ice capacity was recommended.

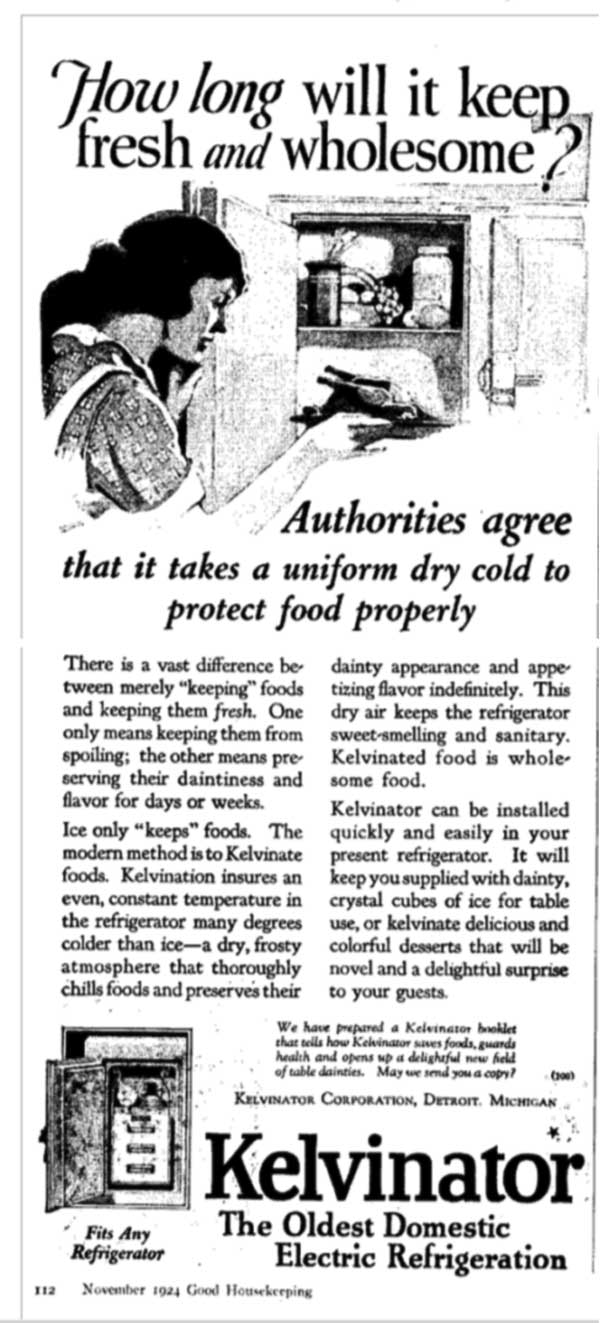

Electric refrigeration became widespread in the 1920s. Approximately 24 refrigerators were introduced for U.S. homes in 1916, with the 1918 Kelvinator being the first refrigerator with automatic control. In addition to the refrigerator as we know it today, cold closets built into kitchen shelving kept food cold but not frozen.

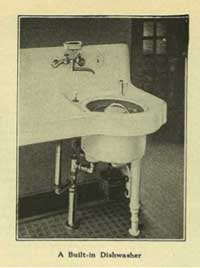

Although not common in the bungalow kitchen, dishwashers were commercially available. They were advertised as the right-hand assistant of the housewife and the healthful alternative to the “insanitary” dishtowel. Tuberculosis was among the top 10 leading causes of death in the U.S. at the time. Numerous times my mother has commented how much easier a dishwasher would have made washing the dishes used by her father, who had TB. Her family needed to boil his dishes to make sure they were sufficiently clean and not a source of transmission.

Although not common in the bungalow kitchen, dishwashers were commercially available. They were advertised as the right-hand assistant of the housewife and the healthful alternative to the “insanitary” dishtowel. Tuberculosis was among the top 10 leading causes of death in the U.S. at the time. Numerous times my mother has commented how much easier a dishwasher would have made washing the dishes used by her father, who had TB. Her family needed to boil his dishes to make sure they were sufficiently clean and not a source of transmission.

Numerous small kitchen appliances also were ushered in with the advent of home electrification. But for me, the refrigerator wins the prize as best electric appliance. A week’s worth of perishable foods kept fresh and a stash of safely frozen items stored away put the fridge at the top of my kitchen convenience list. I am so glad to have all the conveniences of my bungalow back in working order.