Small Home Gazette, Summer 2018

Sheet Music—More Than the Notes

For the first 50 years of the 20th century, you could find sheet music in nearly every U.S. home. The majority of that music was for the latest popular song or dance. From the 1880s through the 1940s, popular culture was unusually cohesive; everyone in the U.S. (with a few regional variations) listened to, played, and sang the same music.

Publishing sheet music was BIG business. Two billion pieces of sheet music were sold in 1910 alone. In the years following, that figure would balloon, only starting to slow in growth in the 1950s as popular culture split into the music factions or genres we experience today.

The first sheet music was published in 1473 but did not take off as an industry until the late 19th century, aided by advancements in printing techniques. The runaway popularity of songs such as “I’m Only a Bird in a Gilded Cage” and “In the Good Old Summertime” (which sold 12 million copies in its first month), convinced many publishers to concentrate on publishing sheet music. Seeing the companies’ profits and realizing they were NOT seeing much of those profits, songwriters such as Harry von Tilzer and Irving Berlin founded their own publishing houses for their compositions and eventually published the songs of others.

A Musical Melting Pot

Popular music at the be- ginning of this time period incorporated elements from a variety of sources. Just as the still relatively young nation was incorporating waves of immigrants, music incorporated the many styles of these immigrant populations.

British immigrants offered a certain simplicity in pastoral and amorous subjects, which became the popular love ballad. Scottish immigrants contributed the “Scotch snap,” a short-long rhythm that reversed the more general long-short rhythm. (Think of the rhythm for the word “comin” in the song “Comin’ Thru the Rye.”) The Italians showed their influence through more lyrical melodies and through accompaniments that imitated the strum of guitars. German contributions included fuller harmonies and a better give and take between the vocal line and the accompaniment. Jewish contributions can be heard in a greater use of minor keys. Africans added new dance rhythms and melodic freedom which eventually became ragtime and jazz.

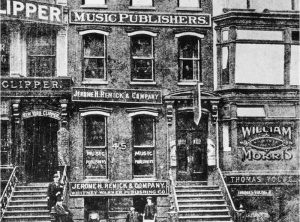

The one city where this blending was most prominent was New York City with its many immigrant neighborhoods. At the end of the 19th century, music publishers were spread throughout the country, with prominent publishers in Philadelphia, Boston, Cincinnati, Baltimore and Chicago. But by the 1920s, Union Square in New York City, at East 14th Street, was the center of the music publishing industry.

Hundreds of song pluggers in that neighborhood would demonstrate on often out-of-tune pianos what they hoped would be the latest hit. Because there was no air conditioning, the din through all of the open windows was dubbed Tin Pan Alley, as legend has it, by composer Monroe Rosenfeld. He may have been commenting on the combined noise, or he may have meant the quality of his fellow composers’ work.

The Notes and More

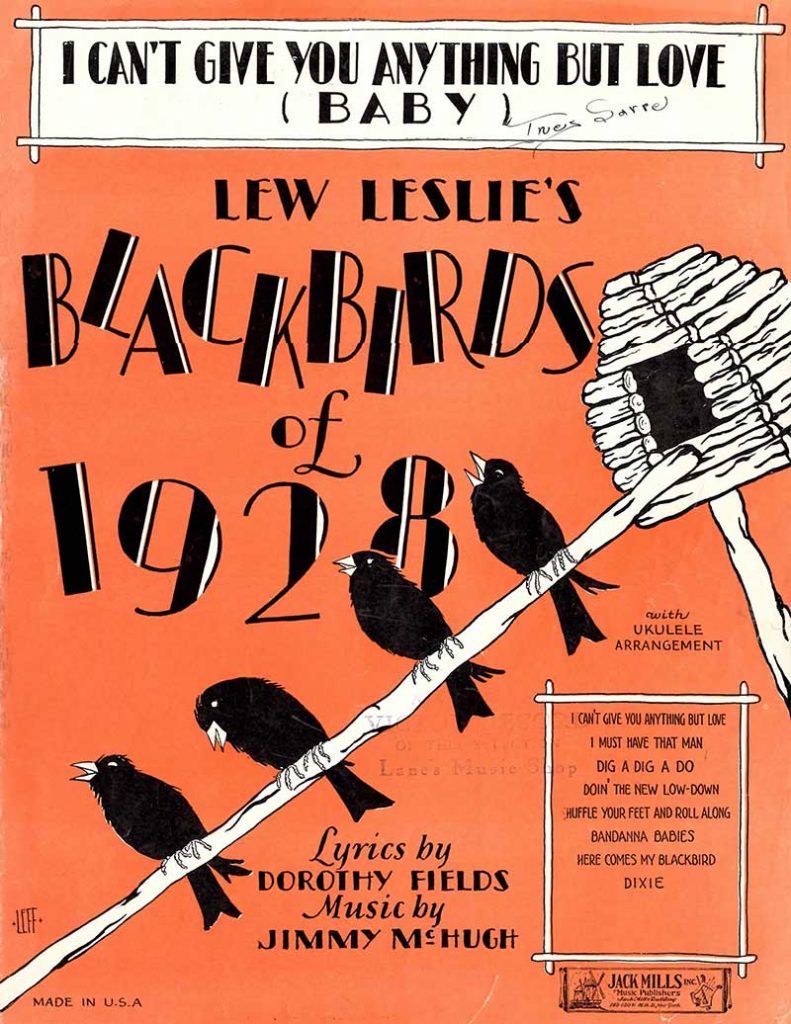

1. Front cover of “I Can’t Give You Anything but Love (Baby)” from the Blackbirds of 1928, a hit Broadway musical revue. Opening on May 9, 1928, it ran for 518 performances, becoming the longest-running all-black show on Broadway.

Sheet music quickly developed into more than just a way to get music to the eager public. The covers of sheet music displayed a lot of information.

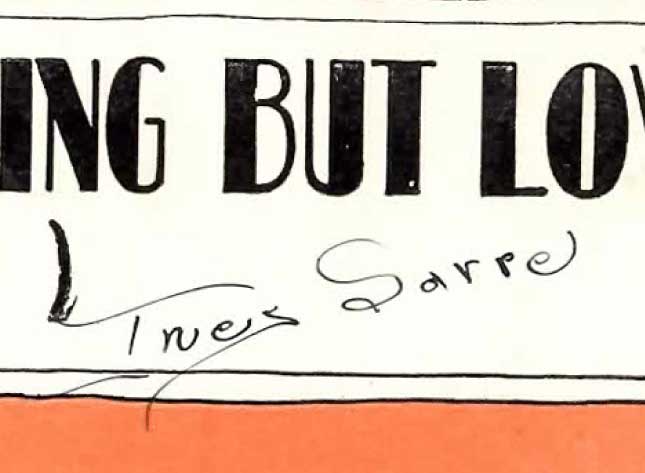

Looking at this particular copy of “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love” (image #1), we see the title of the song splashed across the top of the page, so as to be easily seen in a rack of music.

The next prominent bit of information tells us that this particular song came from a stage production produced by Lew Leslie called “Blackbirds of 1928,” and, looking lower, we see who wrote the lyrics and the music.

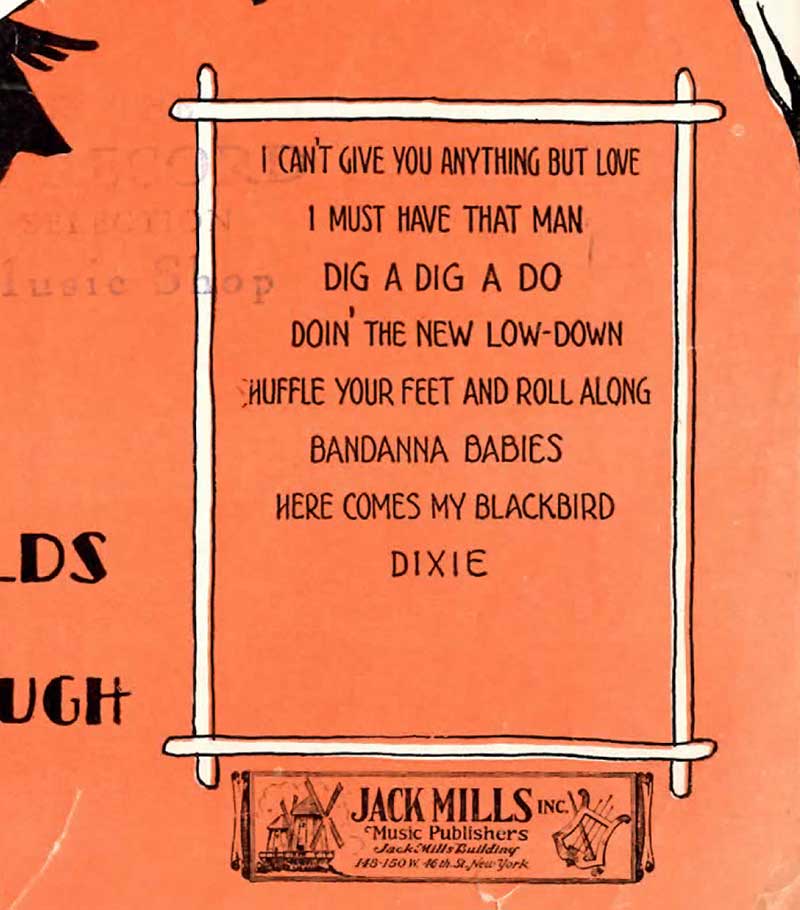

At the bottom right of the cover (#2), are the names of all songs published from this show. Note that the song title at the top of the page also appears in this list. Publishers used one design for all songs from the same show, changing only the title at the top of the cover. The publisher’s imprint (or logo) appears below the list of songs; not to worry, publisher information appears throughout the sheet music so you can’t miss it.

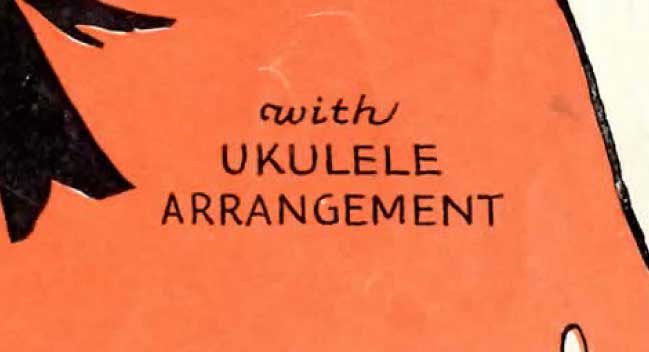

Above the list of songs (#3), wording tells us this piece of sheet music has ukulele chords; they appeared in most sheet music from 1917 to the early 1950s.

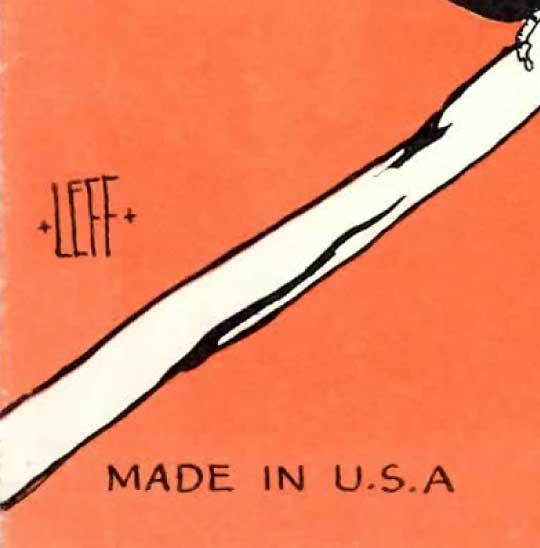

The lower left corner (#4) bears the statement “Made in U.S.A.”; not always found on sheet music but often enough that it appeared to be a concern of the times.

What about the cover illustration? Also in the left corner (#4), just above the tree branch, is the square signature “LEFF” used by Sydney Leff, one of the most important cover illustrators.

Two more items are on this cover. There is a faint rubber-stamp imprint of “Ask for the VICTOR RECORD of this selection Lane’s Music Shop” and, written in fountain pen in the top title box (#5), the name Ines Sarre. This particular copy was purchased at Lane’s Music Shop, perhaps by Sarre herself. It is common to see such stamps, as well as the owner’s name, on the covers of sheet music, revealing that each piece had its own life.

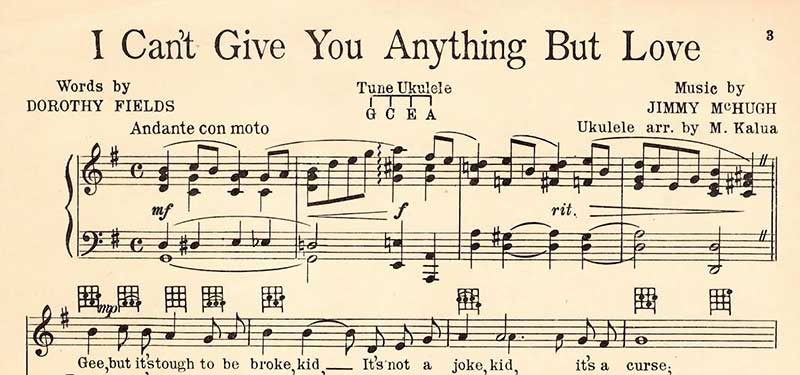

Inside, the first page of the music (#6) includes the title; the lyricist (usually at top left); and the composer (at top right). Just beneath the title, we are told how to tune the ukulele to perform accompaniment to this piece. The funny little squares with the little dots are the ukulele fingerings for each chord. Squares like this with four vertical lines will always be ukulele fingerings; squares with more vertical lines (typically six) will always be guitar chords.

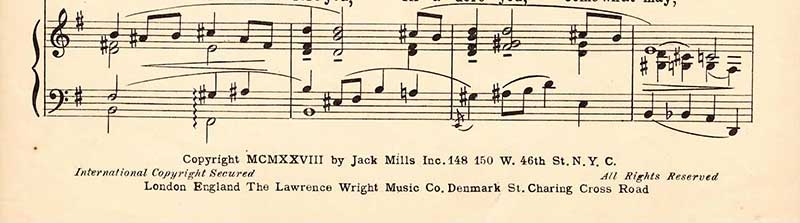

At the bottom (#7) is the publisher (again) with a list of locations, and the obligatory copyright notice. The copyright date, in Roman numerals, is the reason many musicians today can read Roman numerals.

Copyrights in the U.S. were not automatically international. This publisher took care to secure international copyrights. “All Rights Reserved” means the copyright refers to any form of reproduction, from copying the physical sheet music through live, recorded or broadcast performances.

Publishers often added advertising at the end of the song: under the music, sometimes above, and often, as in this case (#8), down the middle of the fold.

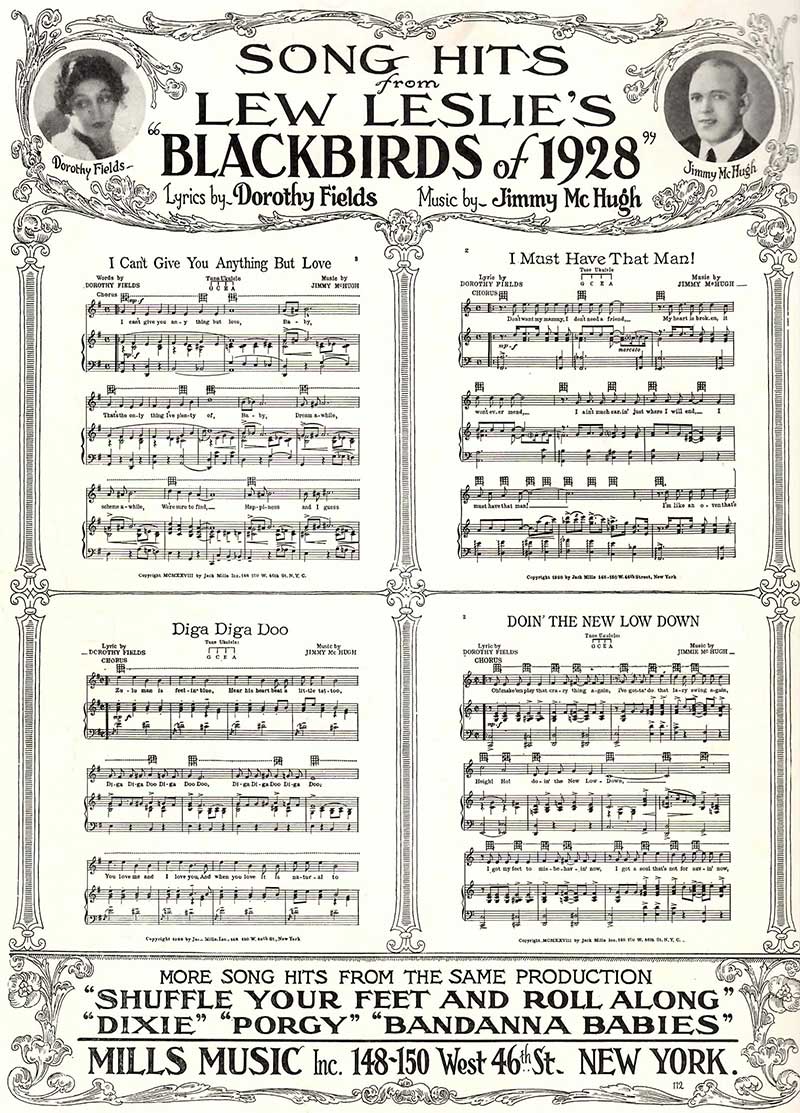

The back of the sheet (#9) was used for more advertising, such as samples of more songs from the show. At the top, we can see photos of the lyricist and composer; these two were lucky. Any photos on the covers, front or back, were often of noted performers (making a piece of sheet music more collectible today). Because this particular piece of sheet music features one of the early all-black (to use the vernacular of the day) Broadway productions, it is yet more collectible. Please note (once again) the publisher’s imprint at the bottom.

Although publishing sheet music had been seen as an ephemeral activity, its existence today reveals much more to the viewer about history than its authors or publishers had ever expected.

Randy Rowoldt is a long-time Bungalow Club member. In addition to working in the costume department at the Childrens’ Theatre Company, he coaches singers of all stripes. Randy started collecting music in his early teens, and his sheet music collection now numbers in the thousands.