Small Home Gazette, Summer 2019

One Long, Two Short—Hello?

Something we share with our bungalow-building ancestors is a fascination with telephones. Early records of the Minneapolis-based Northwestern Telephone Exchange Company show Exponential growth—from 53 subscribers at its founding in 1879 to 3,000 in 1897 to 17,000 in 1908 to nearly 96,000 in 1920.

Something we share with our bungalow-building ancestors is a fascination with telephones. Early records of the Minneapolis-based Northwestern Telephone Exchange Company show Exponential growth—from 53 subscribers at its founding in 1879 to 3,000 in 1897 to 17,000 in 1908 to nearly 96,000 in 1920.

And that was just in Minneapolis. St. Paul had its own telephone service (of course), and while individual phone lines were strung between the cities in the 1800s, regular telephone service between the Twin Cities did not start until 1908. (Read into that what you will.) Long distance lines were mostly a dream until the 1920s. Folks in rural areas would have to wait a while longer for phone service.

Those early telephone lines were a combination of direct connections—picture the businessman paying for a direct line between his home and office—and party lines that linked neighbors together on a single line.

Party Lines

Party lines were common in the first half of the 20th century, especially in rural areas and during the war years, when copper wire was in short supply. A party line was a local telephone loop circuit shared by more than one subscriber.

Note the sand timer attached to the body of the phone—maybe an early way of monitoring the length of a call.

You were assigned a custom sequence of rings, e.g. one long, two short, to indicate that an incoming call was intended for you. Your call would tie up the line for all of your neighbors. Maybe they were listening in. Sometimes your neighbor would jump in to ask you to end your call. Many jurisdictions required a person to immediately hang up if another party needed the line for an emergency call. Authorities (and your neighbors) could ring all the phones on the line to broadcast important news of fires or burglaries or “I need a cup of sugar right now!”

To call someone on the same party line, you dialed their number; hung up your receiver; and gave the person some time to pick up their phone. You then picked up your receiver again and said “Hello?” If no one answered, you waited a bit longer and tried “Hello?” again. If the person called was not answering, you assumed no one was home.

Telephone companies did encourage customers to buy a private line but it was more expensive so few people made the change.

Connecting With People

At first, the telephone was viewed as a toy. People were used to communicating with each other by writing letters (or the ever-popular postcard) or by sending telegrams. Many were fearful that the sounds from telephones could make a person deaf or crazy. And no one liked the idea that other people could listen in on their conversations.

Telephone companies had the challenge of not only selling the new telephone service to people but explaining how they could be useful both in the home and in business—and how they worked.

A handbook for telephone salesmen from 1904 gave reasons for residential customers to put in a telephone: “It is always on duty, shops in all weather, corrects mistakes, and hastens deliveries. It saves letter writing, orders the dinner, invites the guests, reserves the tickets, and calls the carriage. It makes appointments, changes the time, cancels them altogether and renews them. It calls the expressman, calls the cab, and instructs the office. It invites one’s friends, asks them to stay away, asks them to hurry and enables them to invite in return … “

Telephones were promoted to businesses as ways to increase efficiency, save time, and impress customers. But this brand new way of speaking to people without seeing them, as well as the use of party lines, required some tips on manners.

Mind Your Manners

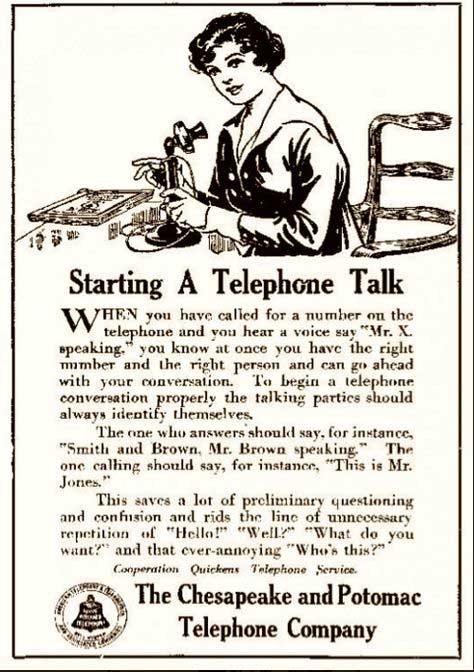

Telephone companies placed informative advertisements in newspapers to help people get more comfortable with using a telephone, and to use it politely. For example, the Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Company (part of the Bell System), which served the Washington, D.C., area, had a series of ads on topics ranging from “Starting a Telephone Talk” to “Finishing a Telephone Talk” to “The Human Element in Telephoning.” The latter explained the role of the switchboard operator.

The messages in these ads seem obvious today. For example, the advice to “start a telephone talk” included:

“The one who answers should say, for instance, “Smith and Brown, Mr. Brown speaking.” The one calling should say, for instance, “This is Mr. Jones.” This saves a lot of preliminary questioning and confusion and rids the line of unnecessary repetition of “Hello!” “Well?” “What do you want?” and that ever-annoying “Who’s this?”

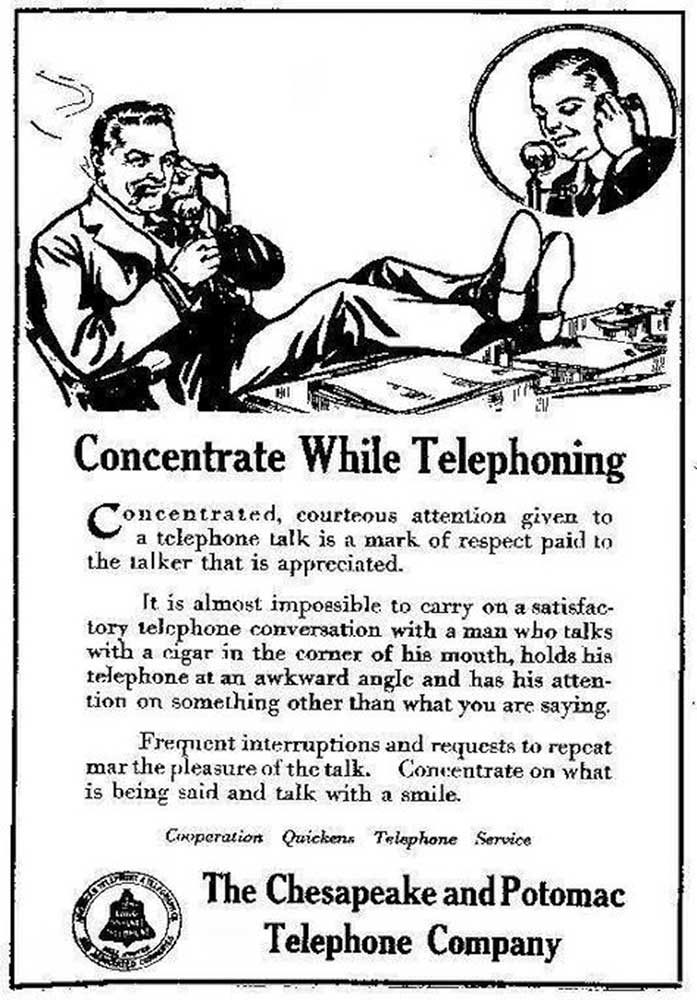

There was even an ad called “Concentrate While Telephoning” which pointed out:

“It is almost impossible to carry on a satisfactory telephone conversation with a man who talks with a cigar in the corner of his mouth; holds his telephone at an awkward angle; and has his attention on something other than what you are saying.”

The Switchboard

In the 1870s, the first telephones for personal and business use were sold in pairs—one for the caller and one for the receiver of the call. If you had multiple clients or friends to call, you would need several pairs of telephones which was, of course, highly impractical. For this reason, manual central switchboard exchanges—and switchboard operators—came onto the scene. And any calls made on anything other than a shared party line had to be connected by an operator.

Initially young boys were hired as operators but proved to be too unruly to do the job. In 1878, Emma Nutt became the first woman telephone exchange operator. Women were seen as being gracious, better-mannered, and cheap to employ. To be hired, a woman had to have good diction and long enough arms to reach the top of the switchboard. (Operators connected calls by inserting a pair of plugs into the appropriate jacks.)

Initially young boys were hired as operators but proved to be too unruly to do the job. In 1878, Emma Nutt became the first woman telephone exchange operator. Women were seen as being gracious, better-mannered, and cheap to employ. To be hired, a woman had to have good diction and long enough arms to reach the top of the switchboard. (Operators connected calls by inserting a pair of plugs into the appropriate jacks.)

She also had to be young and unmarried; the latter being essential because of the 11-hour shifts for six days a week. In small towns, the switchboards were often installed in the operator’s home, as it was considered a 24-hour-a-day job. The typical salary in 1900 was about $7 per week.

By 1919, the switchboard giant Bell System had adopted automatic switching, and it spread throughout the country. But through the early 20th century, operators had to be heavily involved in long-distance calls, instructing the caller to hang up before contacting the operator in the appropriate city; carefully connecting the lines; and calling back. The average time to complete the connection for a domestic long-distance call was 15 minutes.

More Efficient Communication

With the invention of the telephone, people could communicate quickly from great distances. This allowed business practices to speed up and to reach a much wider range of customers. And individuals could communicate with distant family members more easily.

A 1930s survey conclusion is still valid today:

A 1930s survey conclusion is still valid today:

“Most people saw telephoning as accelerating social life, which is another way of saying that telephoning broke isolation and augmented social contacts. A minority felt that telephones served this function too well. These people complained about too much gossip, about unwanted calls, or, as did some family patriarchs, about wives and children chatting too much.”

Sound familiar?