Small Home Gazette, Summer 2020

When Streetcars Ruled the Twin Cities

What follows are two brief articles summarizing the rise and fall of streetcars in the Twin Cities.

Twin City Electric Transit Company and Electric Streetcars

by Linda A. Cameron

Horse car and cable car systems in the Twin Cities spurred urban growth and gave residents more mobility. The coming of the electric streetcar in 1889 had an even greater impact. With cars that could travel faster and farther, the system grew to become one of the nation’s finest public transportation networks before the dominance of automobiles and buses in the 1950s.

The first electric streetcars were developed in the mid-1880s. The new mode of transportation caught on. By 1902, there were 21,902 miles of street railway tracks throughout the United States, with 97 percent of all lines powered by electricity. The electric streetcar earned the nickname “trolley” for the trolley wheel that ran along the overhead wires to power the car.

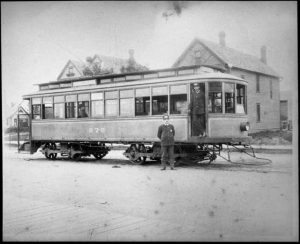

Streetcar in downtown Minneapolis, 1923. Image courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

When Thomas Lowry assumed control of both Minneapolis and St. Paul streetcar companies in 1886, he was reluctant to adopt electrification. The Minneapolis City Council forced Lowry’s hand when it approved the construction of an experimental line by the Thomas-Houston Electric Company. The city mandated that Lowry’s company purchase the line if the demonstration proved successful. Lowry agreed, and the new line entered service on Fourth Avenue South in Minneapolis on December 24, 1889.

Archbishop John Ireland encouraged Lowry to build the first electric lines in St. Paul. The St. Paul City Railway’s first electrified route ran on Grand Avenue on February 22, 1890. Soon, a second line began service on Randolph Avenue.

The public quickly embraced the new technology, but there was speculation about its safety. People were afraid of sparks flying from the wheels and worried that the wires overhead would attract lightning strikes. Drivers of horse-drawn vehicles thought their horses would be electrocuted if they attempted to cross the streetcar tracks. Skeptics believed that the first snowstorm would put the electric cars out of business. The popularity of the lines grew in spite of these concerns. By 1892, the newly incorporated Twin City Rapid Transit Company (TCRT) had converted all horse car routes to electric operation.

The extensive three-year conversion required heavier and wider track, and wider streetcars. New power stations were needed, the first of which was located at the corner of Third Avenue North and Second Street in Minneapolis. The cost of conversion for the two cities totaled $6 million.

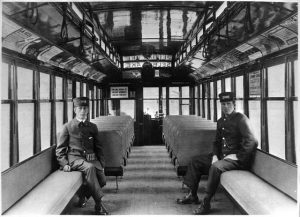

Interior of a streetcar on the Selby-Lake Street line, 1915. Image courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

The first inter-urban route began operation in December 1890, following the old horse car line down University Avenue. The Como-Harriet line opened in July 1898. It ran 17 miles, from Como Park in St. Paul to Lake Harriet in Minneapolis, and cost a dime—two zones at a nickel each. In 1906, the Selby-Lake Street line began service on a route crossing the newly built Lake Street bridge over the Mississippi River. The Snelling-Minnehaha line opened in 1909. That year, TCRT bought the St. Louis Park and Robbinsdale lines, expanding operations to the suburbs.

Advertisement for the “New Doubledecker to Lake Minnetonka,” Minnesota. Twin City Rapid Transit. 1906.

To meet the power needs of the rapidly developing new system, TCRT leased two power stations near the dam just below St. Anthony Falls. The growth of the streetcar system gave riders convenient access to destinations from Wildwood Amusement Park in White Bear Lake to Lake Minnetonka, where it connected with a fleet of express and excursion boats.

Electric streetcars reached their heyday in the 1920s, when TCRT had more than 900 cars running on more than 523 miles of track. Rider-ship peaked in 1920. That year, the company carried a record 238 million passengers, in spite of an increase in the fare from five to six cents—the first increase in TCRT’s history.

Improved roads and the growing popularity of automobiles began to cut into streetcar revenues by the late 1920s. In 1929, TCRT shut down some of its lines and raised the fare to ten cents. To cover its losses, the company purchased local bus companies and a controlling interest in Yellow Cab. Diversifying gave TCRT a monopoly on public transportation in the Twin Cities.

Streetcar on 42nd Avenue South, Minneapolis, Minnesota. 1951.

Encouraged by increased ridership during World War II, 141 sleek new President’s Conference Committee cars entered service between 1945 and 1949. These were short-lived. Rapidly declining ridership in the post-war years prompted new TCRT management to replace streetcars with buses. The last streetcar made a final ceremonial run in Minneapolis on June 19, 1954.

Cameron, Linda A. “Twin City Rapid Transit Company and Electric Streetcars.” Mnopedia, a digital encyclopedia created by the Minnesota Historical Society.

The Streetcar Era in St. Paul

by Paul Nelson

Entrance to the Selby Tunnel, 1948. The St. Paul Cathedral can be seen in the background. Image courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

The electric streetcar service began on Selby Avenue in 1890. St. Anthony Hill, however, proved to be a vexatious impediment; the steep grade made for slow and hard going travel, especially in winter. At about the same time that work began on the Cathedral of St. Paul, the city began digging a solution to the streetcar problem: the Selby Tunnel. It opened in 1907, taking people from the base of St. Anthony Hill beneath Selby Avenue to an opening near Nina Street. Streetcars used the tunnel until their demise in the early 1950s. The tunnel closed in 1959, but its lower entrance can still be seen, just down the slope from the Cathedral.

Streetcar on Grand Avenue in St. Paul, 1910. Image courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

As St. Paul boomed in the late 19th century, housing and commerce marched west across what must have seemed to developers an endlessly spacious prairie. Three streetcar lines ranged west from St. Anthony Hill along the parallel Grand, Rondo and Selby avenues. People filled the neighborhoods, and businesses followed the people, clustering along the three lines. Each of these commercial corridors had its own character. Selby Avenue businesses catered to people’s daily needs: food, clothing and services.

By 1930, roughly the peak of streetcar commerce, there were nearly a hundred businesses on Selby between Western Avenue and Lexington Parkway—groceries, confectioneries, cobblers, movie houses, butchers, pharmacies and dressmakers. The Selby-Dale corner was the hub. At one time there were 26 businesses on a single block. This intersection was also a center of Jewish commerce—proprietors named Levy, Cohen, Braufman, Eisenberg, Herman, and Katz ran stores there.

This article is reprinted with the permission of Saint Paul Historical. Visit them at saintpaulhistorical.com and historicsaintpaul.org.