Small Home Gazette, Summer 2022

Come On In, the Water Is Fine!

“A day at the beach” has come to mean a non-stressful, relaxing day—an easy day. But for women in the mid-1800s, a day at the beach was anything but. What was it like to go to the beach decades later, in the bungalow era?

The 1800s

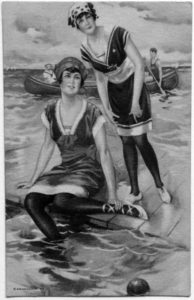

Throughout the 1800s, sea bathing (literally, bathing in the sea for its therapeutic value) became fashionable. With modesty being most important, women’s early bathing costumes were made of a black wool fabric that was not transparent and did not cling to the wearer’s body. These costumes were heavy and were made in two pieces: a long gown that was layered over a pair of ankle-length trousers. Women would wade out into the ocean while holding onto a rope tied to a buoy to keep them from drowning in their bulky garments.

In the mid-1800s, bloomer suits with shortened trousers and short-sleeve tunics became all the rage. With the shorter length trouser, women had to wear stockings and shoes because showing legs was immodest. Unfortunately, bloomer suits were still made with heavy fabrics, mainly wool, but toward the end of the century, the style transitioned to sailor-style suits made of lighter weight fabrics.

In the mid-1800s, bloomer suits with shortened trousers and short-sleeve tunics became all the rage. With the shorter length trouser, women had to wear stockings and shoes because showing legs was immodest. Unfortunately, bloomer suits were still made with heavy fabrics, mainly wool, but toward the end of the century, the style transitioned to sailor-style suits made of lighter weight fabrics.

Early 1900s

By the early 1900s, people (mostly men) were enjoying popular seaside activities such as swimming, playing in the surf, and diving. The only activity for women was still jumping through the waves, still holding onto a rope attached to an off-shore buoy. And their clumsy Victorian bathing costumes were still a burden to wear.

The 1903 pattern included bathing costumes with a blouse and knickerbockers in one, and a full skirt. Options were a sailor, plain or scalloped shawl collar. The bathing costumes could also be made with a high or open neck and full, three-quarter or puff sleeves.

Patterns were offered in magazines such as the 1903 issue of The Delineator. Most patterns included a blouse, knickerbockers (pants gathered and banded just below the knee; also called knickers), and a skirt. In addition to wool mohair, silk taffetas were popular. High necks were preferred to prevent getting a tan line, or a woman could insert a piece of fabric for sun protection. About nine yards of fabric was required to complete the outfit. When wet, a bathing dress of average size weighed 25 pounds.

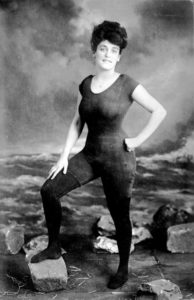

Annette Makes Waves

In 1907, Australian long distance swimmer Annette Kellerman, the first woman to swim across the English Channel, was arrested in Boston for wearing a knee-length, one-piece swimsuit (or unitard) that showed her arms, legs and neck. An early advocate for aerodynamic swimwear, she designed, and was one of the first women to wear, a form-fitting swimsuit. “I want to swim. And I can’t swim wearing more stuff than you hang on a clothesline.”

In 1907, Australian long distance swimmer Annette Kellerman, the first woman to swim across the English Channel, was arrested in Boston for wearing a knee-length, one-piece swimsuit (or unitard) that showed her arms, legs and neck. An early advocate for aerodynamic swimwear, she designed, and was one of the first women to wear, a form-fitting swimsuit. “I want to swim. And I can’t swim wearing more stuff than you hang on a clothesline.”

The interest in swimming as a sport for women, and the demand for a functional, aerodynamic swimsuit, increased when the 1912 summer Olympic games in Stockholm introduced swimming events for women. Fanny Durack, from Australia, claimed the first women’s Olympic swimming gold, wearing a close-fitting swimsuit rather than the heavy, wool costume that had, to quote Durack, “as much drag as a sea anchor.” As a result, sleeveless tunics layered over shorts became the swimsuit style of the day. Women began to go without the required stockings.

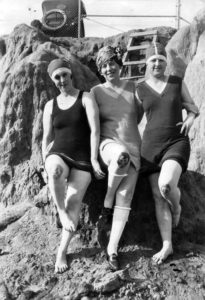

As more women flocked to the beach, the need for a new costume that retained modesty but freed the body enough for swimming was obvious. By the early 1920s, the fashionable bathing suit was reduced to a one-piece garment with a long top that covered shorts.

Movie star Claudette Colbert wears a brown Maillot bathing suit patterned with pink oleander blossoms. Made of satin Lastex.

The 1930s ushered in a new era in bathing suit history. The maillot style of swimwear, which was the first commercial one-piece swimsuit, became the iconic look of the decade. A company named Lastex invented a thin fabric that initially gave support to women in the form of girdles and bras. This new fabric, shiny and sleek, proved to work for swimsuits, too. The suits had lower backs and necklines, and higher cut legs—showing more skin.

And What About Men?

Men’s bathing costumes during the mid-to-late 1800s were boxy, often mimicking undergarments.

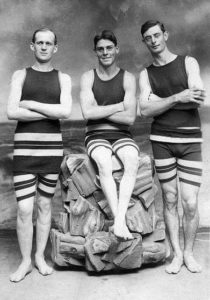

By 1910, most male swimmers wore substantial tank suits with sleeves reaching to the elbows and legs covered to below the knees. These early swimsuits, made from knitted wool, were stretchy (good) but absorbed water (not good).

In many ways, men’s and women’s 1920s swimsuits were nearly identical. Both wore a deep-cut, ribbed wool tank top over a pair of shorts, which were attached at the waistline. The length of the swim top was shorter—coming just to the knee. It was viewed as immodest to raise the top any further for fear of revealing a person’s personal parts. For men, more suit material was removed from under the arms and around the back, making it easier to swim and to reveal more muscles.

In many ways, men’s and women’s 1920s swimsuits were nearly identical. Both wore a deep-cut, ribbed wool tank top over a pair of shorts, which were attached at the waistline. The length of the swim top was shorter—coming just to the knee. It was viewed as immodest to raise the top any further for fear of revealing a person’s personal parts. For men, more suit material was removed from under the arms and around the back, making it easier to swim and to reveal more muscles.

The two-piece swimsuit appeared in about 1922. It consisted of a ribbed wool onesie (unitard) that buttoned at the crotch, paired with separate thigh-length shorts. The onesie top had a scoop neck and was white, gray, striped or bright colors such as red, blue, orange. The shorts either had a button fly with a loose fit or were styled as pull-on ribbed shorts with no fly. A white webbed belt with silver metal military buckle secured the shorts to the waist.

The two-piece swimsuit appeared in about 1922. It consisted of a ribbed wool onesie (unitard) that buttoned at the crotch, paired with separate thigh-length shorts. The onesie top had a scoop neck and was white, gray, striped or bright colors such as red, blue, orange. The shorts either had a button fly with a loose fit or were styled as pull-on ribbed shorts with no fly. A white webbed belt with silver metal military buckle secured the shorts to the waist.

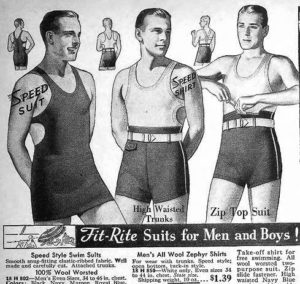

This ad illustrates three styles of men’s suits—the speed suit, a version of the onesie with a speed top, and a zip-top or topper.

In 1929, a new, more revealing one-piece suit emerged, called the “speed suit.” Designed for college athletes, most of the back was removed, and the top was cut out under the arms. This new back was called a “crab back” for its criss-cross pattern. The “speed top” found its way into two-piece swimsuits as well. This style is what would dominate in the 1930s.

Though men were getting the opportunity to look better, there was still the matter of baring the chest. Quite simply, it was frowned upon. By 1933, men were wearing the “Men’s Topper”—a swimsuit made with a “topper” that was fastened to the trunks with a zipper, giving the wearer the option of taking it off. Unfortunately for many of those who did, this led to arrests for indecent exposure. In the late ‘30s, men finally had the right to go topless and could wear the first swim trunks.

Children’s Swimwear

In the mid-to-late 1800s, swimwear for children, just as for adults, was governed by modesty. Boys and girls played in the sand and jumped into waves fully clothed. Swim costumes were buttoned up to the neck, and girls wore bloomers under their skirts. Toward the end of the era, bathing costumes were knitted out of wool—often hand knitted by talented mothers.

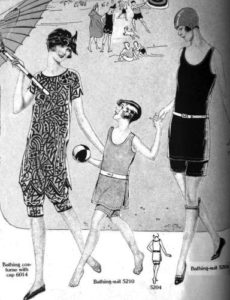

The little girl’s one-piece wool knit suit, Butterick #5210, is as un-fussy as the adult’s bathing suit on the right, #5204.

In the early 1900s, children suits followed the path of adult suits: they became form-fitting and were more comfortable to wear in the water. A Butterick sewing pattern from 1925 showed a woman’s and girl’s style that was shorter, simpler, and sleeveless—a style that would dominate the next few years. The description for the child’s suit states “The suit…should be made of heavy wool jersey. Parents will appreciate the fact that it puts wool next to the youngster’s skin. The bathing suit is practical for girls and little girls 2 to 14 years.” (Imagine a small child wearing “heavy wet wool jersey.”)

Beach Accessories

Swim caps. Early hair coverings were fancy handkerchiefs, caps or a hairnet. Next came taffeta fabric that was waxed to protect hair from dampness. In the early 20th century, swim caps were made of rubberized fabric. The invention of latex had led to the making of stretchier swim caps that fit right in with the head-hugging cloche styles of the Roaring Twenties.

Swim caps. Early hair coverings were fancy handkerchiefs, caps or a hairnet. Next came taffeta fabric that was waxed to protect hair from dampness. In the early 20th century, swim caps were made of rubberized fabric. The invention of latex had led to the making of stretchier swim caps that fit right in with the head-hugging cloche styles of the Roaring Twenties.

The earliest chin strap caps were known as “aviator’s style caps” as they resembled the strapped leather helmets of flyers of the day. Women wore embellished caps as a fashion accessory while women athletes chose plain swim caps.

Bathing shoes and stockings. In the late 1800s, the most common bathing shoe was a cork-soled, low slipper fitted with tapes (or ties) that crossed over the instep and tied around the ankle. As long as bathing costumes covered most of the legs, stockings were not required.

Bathing shoes and stockings. In the late 1800s, the most common bathing shoe was a cork-soled, low slipper fitted with tapes (or ties) that crossed over the instep and tied around the ankle. As long as bathing costumes covered most of the legs, stockings were not required.

As hems got shorter with the introduction of bloomer suits in the early 1900s, black stockings were often worn. Bathing shoes were still the low slipper with the cross-over tapes. About 1915, a new style of bathing footgear appeared—a mid-calf high boot, solid on the sides and back of the leg, but open down the front and laced across the opening.

Closer-fitting, knitted suits appeared in the 1920s, and gradually, the long black stockings were discarded. In the late 1910s and early 1920s, short stockings were worn gartered someplace below the knee, but soon even these disappeared and bare legs began to appear. Bathing shoes were still worn over bare feet when rough ground and hot sand made them desirable, but they were a matter of utility, not modesty.

Men protected their feet with canvas lace-up beach boots or shoes with rubber soles. For most of the 1920s, the all-rubber pull-on swim shoe was the better of the beach shoes because it could be worn while swimming.

Sunglasses. In the 1920s and ‘30s, the eyeglass frame style for both men and women was small round frames made of tortoiseshell or metal. Add tinted lenses and you have the first sunglasses, introduced in the ‘20s. Beach-loving movie stars promoted the new trend, and slowly the public caught on to both the fashion and convenience of lenses tinted dark grey or amber, and even a deep green by the 1930s.

Beach parasols. In the late 1800s, umbrellas were a necessity for rainy days. And they proved to be practical on the beach to protect women’s skin from the sun. Well into the 1900s, the Asian-inspired flat-paper sunshades were all the rage on beaches.

Beach parasols. In the late 1800s, umbrellas were a necessity for rainy days. And they proved to be practical on the beach to protect women’s skin from the sun. Well into the 1900s, the Asian-inspired flat-paper sunshades were all the rage on beaches.

The 1920s brought about a different fashion wave. Instead of protecting the fine complexions of women, the parasol became an impediment to the growing popularity of enjoying a leisure life spent outdoors. Skin tanned by the sun became a symbol of wealth, indicating you had time and money for a vacation. The beach parasol would never regain its status.

Bathing Machines and Beach Police

Until the turn of the 20th century, female bathers got into the water without being seen via a device called the bathing machine. It was a little hut on wheels, with entrances at the front and back. A woman entered while the machine was parked on the beach and changed into her bathing costume. The bathing machine was dragged into the water, by horse or human power. The bather would emerge from the opposite door and step into the ocean, far away from the prying eyes of those on the beach. When done splashing in the waves, she would re-enter the bathing machine, raising a little flag to signal she was ready to return to the beach. Around the turn of the 20th century, as societal opinions relaxed about modesty, bathing machines began to disappear.

Until the turn of the 20th century, female bathers got into the water without being seen via a device called the bathing machine. It was a little hut on wheels, with entrances at the front and back. A woman entered while the machine was parked on the beach and changed into her bathing costume. The bathing machine was dragged into the water, by horse or human power. The bather would emerge from the opposite door and step into the ocean, far away from the prying eyes of those on the beach. When done splashing in the waves, she would re-enter the bathing machine, raising a little flag to signal she was ready to return to the beach. Around the turn of the 20th century, as societal opinions relaxed about modesty, bathing machines began to disappear.

Washington policeman Bill Norton measuring the distance between knee and suit at the Tidal Basin bathing beach. 1922.

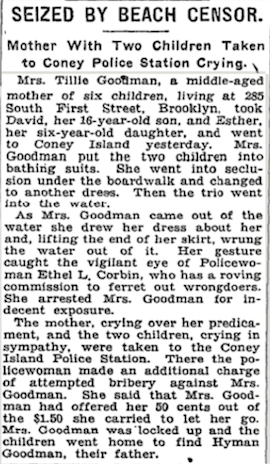

The changes in what was considered appropriate swimwear often conflicted with local laws. During the early 1900s, swimsuit police (sometimes called beach censors) really did roam popular beaches, and women really did face various penalties if their bathing suits did not measure up. As the style of women’s suits changed due to the growing popularity of actual swimming, many local laws were put in place to regulate how much female flesh was visible.

The laws varied. In Washington, D.C., bathing suits could not be shorter than six inches above the knee. In Atlantic City, one-piece bathing suits and bare legs were banned. Coney Island took extreme measures to preserve “decency,” to the point of arresting a woman for wringing out the water of her bathing suit skirt. She showed too much leg in doing so. Chicago hired a “beach tailor” to work with the police to modify inappropriate swimsuits, paying particular attention to armholes and skirt lengths. In Palm Beach, police were told to ban white and flesh-colored stockings and carried a chart containing “every conceivable shade that hosiery experts have judged to come under the heading of ‘flesh-colored.’”

Men may have had a little more freedom, but they were not immune to indecency concerns. Men without shirts were not allowed on the beach in Atlantic City because the city did not want “gorillas on our beaches.” If the men went topless, they could be fined and asked to cover up or, at worst, arrested. (These rules were overturned in 1937.)

The concerns over women’s bathing suits began to subside in the 1930s. Eventually, public standards shifted, and the old regulations came to be seen as absurd. A newspaper reporter in Hammond, Indiana, in 1939, captured the shift in attitude: “The city will establish no rules on type of bathing suits to be worn; just so bathers are garbed in some fashion.”