Small Home Gazette, Winter 2013

A New Generation Discovers Bungalows

Observations by American Bungalow Owner and Publisher John Brinkmann

During their visit, Bungalow Club president Tim Counts asked Brinkmann about the future of bungalows and bungalow neighborhoods.

John Brinkmann: Bungalow neighborhoods, specifically the people who are now buying bungalows, are changing. For a long time the bungalow revival was sparked by the Arts & Crafts revival. Eventually the bungalow itself became an item of interest, more as a style than anything else, connected to the Arts & Crafts lifestyle.

John Brinkmann: Bungalow neighborhoods, specifically the people who are now buying bungalows, are changing. For a long time the bungalow revival was sparked by the Arts & Crafts revival. Eventually the bungalow itself became an item of interest, more as a style than anything else, connected to the Arts & Crafts lifestyle.

But interest in Arts & Crafts, in my opinion, is waning a bit, especially the collecting aspect of it. Bungalows continue to be popular, but we’re seeing a new crowd come into them, for different reasons. It isn’t because they like Arts & Crafts or almond and green kitchens or square brown furniture. It’s because of the lifestyle the bungalow represents.

Tim Counts: What lifestyle is that?

Brinkmann: A lot of the younger people I know are very into organic things. They’re world-conscious. They seem to be less motivated by ostentation than previous generations. Their goal in life isn’t to get a bigger house and then another bigger house and then another bigger house. It’s more about being in tune with who they are and how they live. Some of my friends, for instance, aren’t wealthy at all, but they will spend more for organic foods. By extension, a bungalow becomes right for them because they can have a garden, a little piece of land where they can—not just landscape—but grow organic produce for the table. I think we’re seeing a revival of interest not because of its style or its history, but because it makes sense for their lifestyle.

Counts: Is it also because many bungalows are modest houses? So it’s part of making a smaller footprint?

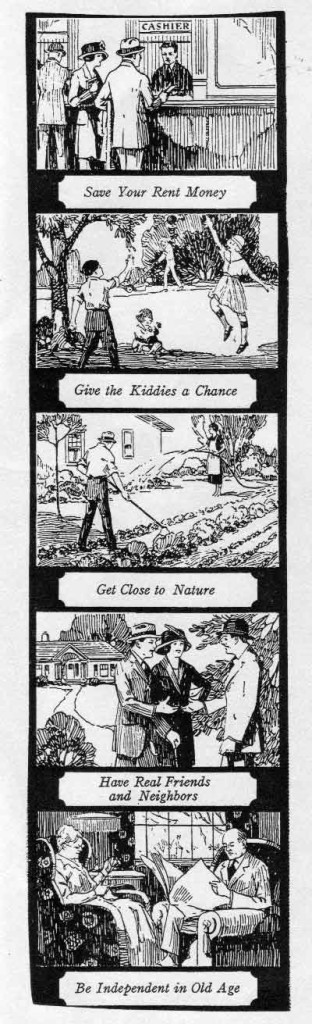

Brinkmann: I think subliminally it is. It goes right back to the original American bungalow concept. Most people didn’t buy bungalows in the ‘teens and ‘twenties because they were connected to the Arts & Crafts movement. Perhaps the very first people who got into them—those who had high-end, architect-designed bungalows—may have had that in mind. They were making a fashion statement and a lifestyle statement at the same time. But most bungalows were originally purchased by people who had moved off the farm or out of brownstones, people who were looking for a place they could manage and have to themselves.

Brinkmann: I think subliminally it is. It goes right back to the original American bungalow concept. Most people didn’t buy bungalows in the ‘teens and ‘twenties because they were connected to the Arts & Crafts movement. Perhaps the very first people who got into them—those who had high-end, architect-designed bungalows—may have had that in mind. They were making a fashion statement and a lifestyle statement at the same time. But most bungalows were originally purchased by people who had moved off the farm or out of brownstones, people who were looking for a place they could manage and have to themselves.

I think that’s what we’re seeing again, but it’s for different reasons. These new people are really socially aware. The influx of this new generation is not anything major at this point, but it surprises me how often, when I explain what American Bungalow is all about, people who have never given a thought to bungalows, say, “That’s the kind of house I want. That’s the life we’re looking for.”

Counts: What it is that they are attracted to? You mentioned the garden. What are other things they key into that aren’t necessarily connected to the roots of the British Arts & Crafts movement?

Brinkmann: I don’t think they know much about the movement. But they do know that the house is relatively small and easy to heat, and that they may not even need air conditioning. Bungalows are space efficient. They make sense. These people are looking for a sensible lifestyle. It isn’t the concept of the bungalow that interests them. It’s the concept that is built into the bungalow. The very efficiency—the efficient use of space appeals to this new generation. On the other hand, I think a lot of the people who moved into them earlier, in the 1980s and ‘90s, did so out of economic necessity.

Counts: One of the primary reasons I chose my bungalow is because it was cheap.

Brinkmann: And then you discovered all the cool things that go with it. That happened to a lot of our readers. When the magazine started in 1990, there was a housing slowdown, so people had to buy smaller homes. But then they said, “This isn’t bad at all, this is kind of neat. And it looks like my grandma’s house.” It wasn’t long before the homey-ness of it became apparent. So a popularity of the style helped propel that original bungalow revival. This new group I’m talking about doesn’t know about the style, or they don’t care about it particularly. Theirs isn’t a style statement; it’s a practicality statement.

That’s where we’re tilting American Bungalow magazine a bit. We’re featuring more small bungalows with gardens. Frankly, I don’t know whether many of the people who live in bungalows for that reason will ever subscribe. We may, for all time, be tied to Arts & Crafts collectors and people who appreciate vintage things. I don’t think these new bungalow people are necessarily concerned whether they have craftsman furniture or not, but they do appreciate quality and authenticity and art, so they are potential converts.

Counts: I think many of those who built these houses were not keyed into the tenets of the British Arts & Crafts movement either. These were the mass produced houses of their day. Sears kit homes were a far cry from William Morris’ philosophy of artistic handcrafted goods. The people who built our bungalows were flipping through catalogs, saying, “Give me a model number 753A.”

Brinkmann: I think our Arts & Crafts movement is really quite divorced from the British movement. In order to give the philosophy merit, we have sort of reconnected to the Arts & Crafts movement in England, but William Morris never made anything that an average guy could afford. The British Arts & Crafts movement may have given a toehold in this country to Arts & Crafts enthusiasm, but it was really Gustav Stickley’s craftsman interpretation that did it here. His message was about honesty and true workmanship, a lack of ostentation, and a celebration of the human relationship with natural materials. “Look,” people said, “you can see how he put this together; here’s the joinery.” That still speaks to people.