Small Home Gazette, Winter 2018

The Golden Age of the Piano

Musical ability was considered such a valuable skill in society that music was a core part of education. The 1905 Sears and Roebuck catalogue had 60 pages of musical instruments for sale—twice the number of pages offering stoves for sale.

Thousands of companies with names such as Aeolian, American Piano Company, Bechstein, Becker Brothers, Chickering, Kimball, Knabe, and Steinway built the pianos that adorned American homes. There is no definitive number of piano manufacturers from this time. Out of the thousands of companies building pianos at the start of the 20th Century, only a handful are still producing today.

Thousands of companies with names such as Aeolian, American Piano Company, Bechstein, Becker Brothers, Chickering, Kimball, Knabe, and Steinway built the pianos that adorned American homes. There is no definitive number of piano manufacturers from this time. Out of the thousands of companies building pianos at the start of the 20th Century, only a handful are still producing today.

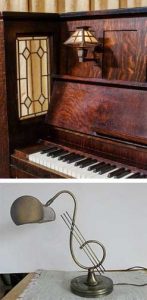

The majority of pianos built for the American home were upright pianos, which were cheaper than grand pianos and took up less floor space. Soon special alcoves appeared in houses and apartments to accommodate an upright piano. These alcoves were often dark and, combined with the dimmer lighting of the period, it was difficult to read sheet music.

So, the piano window was born—usually two or three small square casement windows in the upper reaches of the wall so as to be above the top of an upright piano. While many of us have piano windows in our bungalows, you may have them elsewhere in your home. Architects realized this style of windows offered light over built-in buffets and over the home’s ice box (which often had its own alcove).

So, the piano window was born—usually two or three small square casement windows in the upper reaches of the wall so as to be above the top of an upright piano. While many of us have piano windows in our bungalows, you may have them elsewhere in your home. Architects realized this style of windows offered light over built-in buffets and over the home’s ice box (which often had its own alcove).

The sheer number of pianos in American homes spurred growth in related industries. Not every piano came with a piano bench. Some piano manufacturers offered benches that matched the style of the piano. But often when you purchased a piano, you had to buy a bench separately. Consumers on a tight budget opted not to buy a bench but, instead, pulled a dining or kitchen chair up to the piano to play.

The sheer number of pianos in American homes spurred growth in related industries. Not every piano came with a piano bench. Some piano manufacturers offered benches that matched the style of the piano. But often when you purchased a piano, you had to buy a bench separately. Consumers on a tight budget opted not to buy a bench but, instead, pulled a dining or kitchen chair up to the piano to play.

Some piano benches had seats that could be raised so that sheet music could be stored in the bench. A nice idea, but most households acquired more sheet music than the storage in the bench could hold. Thus was born the first incarnation of the music cabinet, usually a chest on short legs, with narrow horizontal shelves in which to store your music. When the record player started to displace the piano in the home, the music cabinet was restructured to hold round records. Many of the music cabinets one finds in antique stores today were manufactured for recordings and not for sheet music, although there must have been a lot of overlap in usage.

Some piano benches had seats that could be raised so that sheet music could be stored in the bench. A nice idea, but most households acquired more sheet music than the storage in the bench could hold. Thus was born the first incarnation of the music cabinet, usually a chest on short legs, with narrow horizontal shelves in which to store your music. When the record player started to displace the piano in the home, the music cabinet was restructured to hold round records. Many of the music cabinets one finds in antique stores today were manufactured for recordings and not for sheet music, although there must have been a lot of overlap in usage.

When no longer in vogue for the top of the piano, the piano shawl became a fashion item. Woman’s Home Companion, January 1928.

Textile manufacturers developed special drapes or throws to cover the top of the piano. There was a craze in the 19th century to use paisley cashmere or embroidered ”Spanish” shawls to cover your piano to demonstrate one’s cosmopolitan nature. The craze for shawls had pretty much died out by the 20th century, but manufacturers had already started offering special piano cloths cut large enough to hang over the sides and front. These edges usually had an embroidered border.

Lighting manufacturers had already developed candle sconces that could be attached to the front of an upright piano. As electricity spread into homes, the addition of electrical cords to these sconces would be unwieldy. The piano lamp was the solution—placed on top of the piano, with a long bulb on an arm that could extend over the edge of the piano and light the music in the piano rack.

Lighting manufacturers had already developed candle sconces that could be attached to the front of an upright piano. As electricity spread into homes, the addition of electrical cords to these sconces would be unwieldy. The piano lamp was the solution—placed on top of the piano, with a long bulb on an arm that could extend over the edge of the piano and light the music in the piano rack.

The sovereignty of the piano in the early 20th century home was not really challenged by the record player until the early 1920s when the cost of a piano had risen considerably, while the cost of the record player had fallen. You could buy a piano at that time for $15 down and $12 a month for 36 months, for a total of $445. Or you could buy a record player for $5 down and $5 a month for 8 months, for a total of $43.50. For comparison, you could buy a refrigerator for $87.50 or a washing machine for $97.50.

Prices like these doomed the piano’s central focus in the early 20th century home. The rise of radio in the 1920s and, in particular, the development of longer broadcasting hours and commercial broadcasting stations, finished off the piano’s dominance. People no longer valued making their own music at home in favor of listening to others make music. With the piano no longer central in the home, we lost more than just a bulky piece of furniture—we lost camaraderie and family togetherness.

Most people don’t associate pianos with the Arts & Crafts movement, and for good reason. Established piano makers of the late 1800s didn’t see the movement coming, and by the time they did, it wasn’t economical for them to go through the rigors and cost of designing and marketing this “new” style of piano. As a result, relatively few pianos in the Arts & Crafts style were produced and very few of those pianos are around today. Below are examples of styles that were available.