Small Home Gazette, Winter 2021

Lighting Comes Home

At a brownstone on 24th Street in south Minneapolis, the bulb in the front porch lighting fixture has been replaced. The new bulb looks convincingly like a gas jet—appropriate for buildings built around 1900, a time when most houses were lit by gas. Some apartments in this neighborhood still have dual-source lighting fixtures inside, although the gas has long been turned off.

At a brownstone on 24th Street in south Minneapolis, the bulb in the front porch lighting fixture has been replaced. The new bulb looks convincingly like a gas jet—appropriate for buildings built around 1900, a time when most houses were lit by gas. Some apartments in this neighborhood still have dual-source lighting fixtures inside, although the gas has long been turned off.

Gas lighting dictated some of the design of late 19th century buildings. Ceilings had to be high, an average of 13 feet, to allow heat and fumes to circulate above people’s heads. Double-hung windows, with the top and bottom panes both opened, allowed the noxious burn-off from gas lighting to flow out of the top section of the window and clean air to circulate in through the bottom. (The air flow in bungalows might be improved by doing this today.)

Because the light from gas fixtures dispersed in all directions, ceilings were not needed to bounce light and could be papered, stenciled or have a texture added to the plaster as much as Victorian walls. Darker ceilings and walls also helped hide the smoke residue deposited by the light fixtures. The shades on gas fixtures opened to the ceilings to allow the heat to rise. Most rooms were lit by a central chandelier, supplemented by the occasional wall sconce. (Wall sconces are an interesting holdover from times when castles had brackets mounted on the walls in which one placed their torch upon entering the room.)

Because the light from gas fixtures dispersed in all directions, ceilings were not needed to bounce light and could be papered, stenciled or have a texture added to the plaster as much as Victorian walls. Darker ceilings and walls also helped hide the smoke residue deposited by the light fixtures. The shades on gas fixtures opened to the ceilings to allow the heat to rise. Most rooms were lit by a central chandelier, supplemented by the occasional wall sconce. (Wall sconces are an interesting holdover from times when castles had brackets mounted on the walls in which one placed their torch upon entering the room.)

Electric lighting was available and used in commercial buildings much earlier in the 19th century than it was in private homes. Paris experimented with arc lighting on its streets in 1841, but the bright, harsh, blue lighting was not popular. Some factories, and even a few of the newly-developed department stores, began to be lit by a combination of gas and electric fixtures by the end of the 1880s. There was no comprehensive electrical grid at the time, so businesses and homes had to install gasoline- or water-powered generators. Installing an electric generator in one’s home was very expensive, and thus, an extreme example of “conspicuous consumption” in this era.

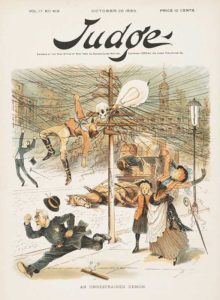

A Judge magazine cover, from October 1889, illustrates how not everyone trusted electricity. The caption reads, “An Unrestrained Demon.”

Most people resisted electricity for many years. It was bad enough that the early light bulbs emitted a very harsh light but it was thought that one could be electrocuted by touching a light switch or fixture, or that it was otherwise inherently unsafe. A few believed that electric light was one cause of freckles. People also feared that the electrical current would cause fires. Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt removed the electrical system she had recently had installed in her Fifth Avenue mansion in New York City because of a fire. In truth, electrical lighting was much safer than gas lighting. Much more to the point, unless you were fabulously wealthy, electricity was priced out of your reach.

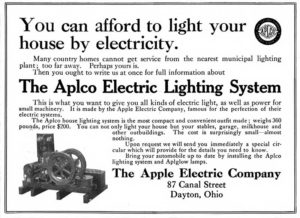

Magazines frequently advertised home generators. Note that the wording in this ad begins with “Many country homes…,” which referred to what we now think of as the suburbs.

By 1900, more homeowners were willing to experiment with electricity in their homes, although they still had to install generators in their basement, or elsewhere in the home such as a closet. Home magazines from the first decade of the 20th century had few advertisements for lighting fixtures of any type, and fewer articles giving instructions on how to light your home, but they did have the occasional advertisement for home electrical generators. By the end of the decade, many towns, and many of the new housing developments that were appearing, began to advertise a cohesive electrical grid as one of their major drawing cards. Modernity was here!

Most homes built from 1900 until the early ‘teens were built to be lit by gas AND electricity. Many of the light fixtures in these homes were “dual-source” fixtures—one shade covering a gas jet (facing up) and a second shade to cover the electric light bulb (facing down). In the movie Meet Me in St. Louis (set in 1903), watch Judy Garland and her young man turn off the lights at the end of a party. First, she turns a round dial on the wall to turn out the electrical half of the chandelier. (Look for the electrical wire running up the wall to the chandelier, which indicates the house had been retrofitted for electricity.) Then the two use a rod with a hook on the end to turn the valve off on the bottom of each of the gas jets.

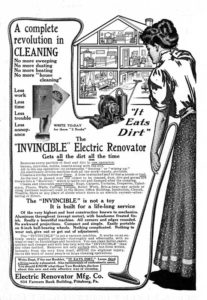

“A complete revolution in CLEANING” states an ad for the Electric Renovator in the American Homes and Gardens magazine, October 1908. Note the cord hookup to a generator.

Electricity started to be standard in urban homes between 1910 and 1920. Much of the change in acceptance came from the many labor-saving electrical devices that were being developed, first and foremost the electric vacuum cleaner, also known as the “electric renovator.” In 1914, American Homes and Gardens magazine declared that electrical devices “solved the servant problem.” Electricity was now thought to be cleaner and economical. (Read this article, plus a second entitled “To Lessen Kitchen Labor,” on the Twin Cities Bungalow Club website.)

Some of the new electrical devices advertised for the home were: toaster, instrument sterilizer, shaving cup, curling iron, dish washer, coffee percolator, cereal cooker/glue pot, hot plate, clothes washer, and even a closet to sit in to receive an electrical treatment for “the betterment of one’s health.” Electric “cookers,” or electric range and oven combinations, were advertised as being complete with timers that the housewife could set to start and stop cooking at given times. This allowed the housewife to prepare dinner and leave her home to do some shopping (or gossiping), confident that the family dinner would be started on time while she was gone. The combination cereal cooker/glue pot was intended to prepare the oatmeal for breakfast right at the dining room table and could later be used to prepare the animal-based glue used in home repairs.

Some of the new electrical devices advertised for the home were: toaster, instrument sterilizer, shaving cup, curling iron, dish washer, coffee percolator, cereal cooker/glue pot, hot plate, clothes washer, and even a closet to sit in to receive an electrical treatment for “the betterment of one’s health.” Electric “cookers,” or electric range and oven combinations, were advertised as being complete with timers that the housewife could set to start and stop cooking at given times. This allowed the housewife to prepare dinner and leave her home to do some shopping (or gossiping), confident that the family dinner would be started on time while she was gone. The combination cereal cooker/glue pot was intended to prepare the oatmeal for breakfast right at the dining room table and could later be used to prepare the animal-based glue used in home repairs.

These are examples of the first type of plugs and sockets used in the home. Note the cover for the floor socket—similar to the covered sockets for today’s outdoor electricity.

All of these appliances had different plugs, depending on the company of their manufacture. The most commonly used was one developed by Edison in the 1880s. The plug looked like the screw end of a light bulb with a braided cord coming out where the bulb should have been. Electrical outlets, if the house had them, were round and stuck out of the wall. A person would screw the plug into the outlet just as one would screw in a light bulb. (These outlets can even be seen in many of the early Mickey Mouse cartoons, usually flashing by in the baseboard during a chase sequence.)

“Extra outlets” meant homemakers no longer had to choose between using their new electrical appliances and keeping the lights on. Ad is from the American Cookery magazine, 1919.

Often one had to remove the light bulb from its socket and screw the appliance into the socket of the light fixture. Dining rooms often had this kind of socket mounted into the middle of the dining room floor. Homeowners would cut a small slit in the middle of the carpet under the dining table so they could plug in a table light. The cord would run from the light fixture down a table leg to the outlet in the floor. This avoided having an electrical cord running across the room over which one could trip. The pronged plugs on electrical appliances with which we are familiar today were a later development and were not standardized until the electrical grid was standardized.

Electric lighting meant that the high ceilings of the past could be lowered to eight or nine feet. Most rooms no longer needed a central chandelier; the chandelier that remained became the light fixture over the dining room table, usually a basin directing the light up for indirectly lighting the entire room, or a “cascade” or “shower” fixture of multiple bulbs hanging downward.

Electric lighting meant that the high ceilings of the past could be lowered to eight or nine feet. Most rooms no longer needed a central chandelier; the chandelier that remained became the light fixture over the dining room table, usually a basin directing the light up for indirectly lighting the entire room, or a “cascade” or “shower” fixture of multiple bulbs hanging downward.

Wall sconces became extremely popular, perhaps the last reminder of castle life. Sconces and most ceiling fixtures threw their light up and depended on the ceiling now being painted white to bounce more light back into the room. Several guides for lighting suggested that, for best illumination, sconces be mounted 5′6″ to 5′8″ from the floor to avoid disagreeable shadows.

You can buy the hardware for a floor outlet today. Available in several shapes and finishes, today’s versions are two-prong outlets rather than the originals which were designed to receive a screw-in type of plug.

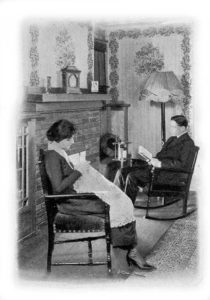

Most other lighting became moveable. In the living room, table lamps could be carried from one spot to another, as long as there was an electrical outlet available. It was thought that a brightly lit room was worse than a too dimly lit room. The ideal lighting of a living room was to provide smaller pools of light highlighting areas for separate activities within the room. Likewise, the furniture in the living room was often arranged to allow separate reading or conversation areas.

When houses were still lit by candles, kerosene or gas lamps, the family would, out of necessity, gather in the living room in the evening to conserve their source of light. Electric lighting allowed every room in the house to be lit separately and at the same time. This meant that the family would no longer have to gather in one room. Electrical appliances meant that the number of hours a housewife would spend in housework declined, giving the homemaker a greater freedom and breaking many of the ties that held her to the house.

The advent of electricity in bungalows changed home interiors in significant ways and altered how families interacted. History shows that electricity helped to start us down a path toward isolation between family members. That process started when electricity, like computers, was first feared, and then embraced, to finally being ubiquitous in our homes.

The advent of electricity in bungalows changed home interiors in significant ways and altered how families interacted. History shows that electricity helped to start us down a path toward isolation between family members. That process started when electricity, like computers, was first feared, and then embraced, to finally being ubiquitous in our homes.

Randy Rowoldt is a long-time Bungalow Club member. In addition to working in the costume department at the Childrens’ Theatre Company, he coaches singers of all stripes.