Small Home Gazette, Winter 2022

Very Special Deliveries

On January 1, 1913, the U.S. Postal Service introduced Parcel Post to its list of mail services, allowing the shipping of large packages through the mail. Before then, all packages sent by mail had to weigh four pounds or less. People could now ship anything up to 11 pounds. Eventually the limit was raised to 50 pounds.

Using the new service meant learning new rules. Packages could be turned away if not wrapped according to U.S. Postal Service instructions.

A package’s journey started at the post office window and involved scales, stamps and money. It was then sorted for local carriers to deliver, using vehicles or, in rural areas, horse carts. For a delivery across the country, mail trains were a critical part of the system in the early 1900s. The inside of a mail car operated much like the back room of a post office where sacks of mail were sorted.

Private delivery companies had flourished during the 19th century, but the Parcel Post service, along with the advent of cars and mail trains, dramatically expanded the reach of mail-order companies such as Sears, Roebuck and Co. and Montgomery Ward to America’s many rural communities. Regulations about what could and could not be sent through the mail were vague. Items accepted depended on how the local postmaster interpreted and applied the regulations.

People quickly began ordering products but also mailing to each other. Items mailed ranged from parasols to pitchforks, eggs to bricks—AND babies and small children.

Jesse and Mathilde Beague of Ohio used the service the first month it was in operation. They mailed their eight-month-old son James to his grandmother who lived several miles away. The cost was 15 cents for stamps and an unknown amount for $50 of insurance (in case the postal carrier lost him). James was handed over to the postal carrier and delivered safe and sound to his grandmother.

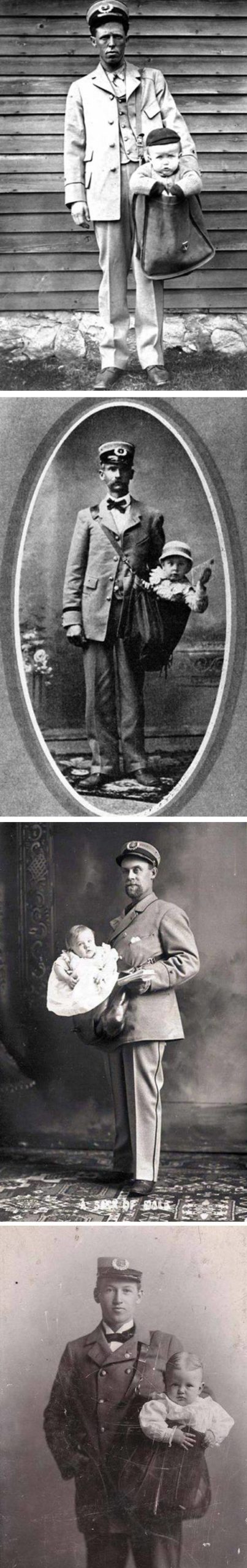

The practice of mailing babies drew a lot of attention. These photos were staged for publicity purposes. There is no record of a child being delivered in a mail pouch.

Keep in mind, people who mailed their children were not handing them to a stranger. In rural areas, families knew the postal carriers as friends and relatives. There is no record of a baby or child being lost in transit.

In February 1914, six-year-old May Pierstorff was also sent to a grandmother, 73 miles away. The Idaho family paid 53 cents for stamps that were attached to May’s coat. It was cheaper to send a child using the Railway Mail Service in a mail car than to buy a ticket on a passenger train. The postal worker who took her by Railway Mail was a relative.

After Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson heard about May’s journey, he officially banned postal workers from accepting humans as mail. Despite this declaration, at least five more children were known to be mailed well into 1915.

The longest trip taken by a “mailed” child was in 1915 when six-year-old Edna Neff traveled from her mother’s home in Florida to her father’s home in Virginia. The nearly 50-pound girl made the 720-mile trip on a mail train for just 15 cents in parcel post stamps. Little is known about the specifics of Edna’s trip.

In August 1915, three-year-old Maud Smith made what was thought to be the last journey of a child mailed by parcel post. Her grandparents in Kentucky mailed her over 40 miles to be with a sick mother. The postmaster who allowed Maude on a mail train was questioned and most certainly disciplined.

BUT according to an article published in the Springfield, Missouri, Republican on September 3, 1918, mailing children still occurred three years after little Maud’s trip:

“Josephine McCall, 7 years old, and Iris Carter, 8 years old, have been stamped, mailed and yes delivered by the parcel post from their home in Red Top to their aunt, Mrs. Bessie McCall, 1221 North Campbell Street, Springfield. They came all the way in one of the new motor trucks over one of the new routes and were driven by W. E. Fawcett who delivered them.

The children were weighed and the cost of sending them figured at the regular rates of sending things. Josephine, it was found could go for 52 cents but it took 70 cents to pay for the mailing and delivery of Iris.

A dollar and twenty-three cents was paid and the children were stamped like ordinary parcels. When the driver of the new motor truck, W. E. Fawcett, came steaming into Red Top, he found the two children awaiting him along with other things he was to deliver to Springfield.”

In June 1920, First Assistant Postmaster John C. Koons rejected two applications to mail children via parcel post. In a New York Times article published on June 14, Koons stated that “…children did not come within the classification of harmless live animals which do not require food or water while in transport.”

Eventually people stopped trying to send children by post. But it was a practice that showed how the U.S. Postal Service and its postal carriers were a connection between family members living apart from each other. And Americans, especially in rural areas and small towns, entrusted the lives of their children to the service.